A year ago, we described India as one of the fastest expanding economies in the world with growth rates of 7%. Today, the world looks totally different: India is still grappling with rising numbers of Covid-19 infections; lockdowns have been extended for the fourth time, now until the end of May; and analysts expect the economic output to shrink by up to 5% in 2020.

However, no matter how dire the situation is, Prime Minister Modis’ approval ratings are rising. Could he really emerge as beneficiary from the crisis and possibly seize the moment by pushing through the promised reforms? Or could he even use the tensions between the Western world and China to strengthen India’s position in the global supply chain?

Prime minister confronted with growing number of problems

Shortly prior to the outbreak of the corona crisis, the situation in India looked completely different: Narendra Modi was confronted with a growing number of problems on multiple fronts. When he came to power six years ago, he positioned himself as reformer who wanted to implement overdue changes. Some of his plans were put into action, whereas with others such as the land reform he has had to back-pedal recently. Either way, the changes have not come with the desired macro-economic results. Overall, Modi has so far promised more than he has kept.

In addition, we saw tensions rise between the various population groups last year. Politically, Modi is following a clearly more nationalist path, which appeals to the Hindu majority (about 80% of the population). A negative climax was reached at the end of February when 50 people were killed amid clashes between Hindu and Muslim citizens in a part of Delhi. The conflict with Pakistan about the Kashmir region remains unresolved.

High approval ratings among the people

Paradoxically, Prime Minister Modi seems to be able to benefit from these adverse conditions. In opinion polls some 80-90% of the population have recently approved of his current policies. In contrast to Western heads of state, Prime Minister Modi never doubted or put into perspective the danger the virus presents for India. And the prime minister clearly knows how to put bitter medicine in a shiny bottle: at the end of March, he announced the nationwide lockdown only four hours before it came into effect, and it was still obeyed by large parts of the population – the fact that only about 500 people were known to have been infected across the country notwithstanding. That being said, the performance of the government during the pandemic is not without flaws: the lockdown led to an immediate loss in jobs and income of tens of thousands of migrant workers. Given that they were also unable to return to their villages (N.B. cross-regional traffic had been suspended as well), many are now left financially high and dry.

As soon as the restrictions can be lifted, the extent of the economic crisis will become clear. In April, more than 120 million people lost their jobs, and the unemployment rate increased significantly from 8.5% in March to about 24% at the end of April. Despite its volume of USD 260bn (i.e. 10% of GDP), the relief package announced in mid-May might not be enough. Direct payments and help for the poorest only make up a small part of the measures as well.

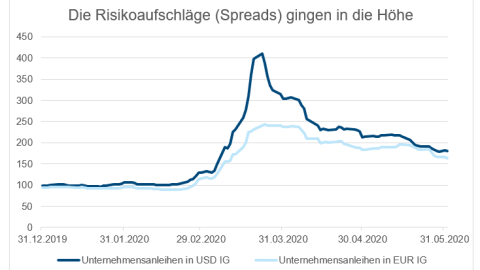

Elevated spread on Indian companies with good to very good ratings

Spreads of Indian corporate bonds in comparison with all emerging markets corporate bonds with good to very good ratings in bps

| Mai 2020 | 262,5 |

| Mai 2019 | 187,3 |

| Mai 2018 | 197,5 |

| Mai 2017 | 177,7 |

| Mai 2016 | 240,9 |

Sources: Bloomberg, JPM Indices; N.B. 100 basis points are 1 percentage point

Far-reaching reforms

Instead, Modi wants to use the crisis also to quickly implement the reforms that have been announced for years. They include in particular the massive deregulation of the agricultural sector. Here, the prime minister has hinted among other steps at the complete abolishment of trade barriers between the various Indian states and the farmers’ right to freely sell their goods.

Thus, the current situation could offer another historic opportunity for far-reaching reforms. The year 1991 can serve as benchmark here: back then, India was in the grip of a currency crisis. The rulers at the time seized that difficult phase to implement crucial reforms. Retrospectively, 1991 was a year of profound change, because the liberalisation and deregulation that was implemented turned India into a market-based economy. This was the foundation for significant foreign investments and the subsequent economic rise.

In addition, Prime Minister Modi also announced his intention to re-position his country globally. Against the backdrop of the persistent trade conflict between China and the USA and the emerging trend of diversifying one’s production locations, India could become an interesting alternative for Western industrial companies to take up residence (again). The shift of the global trade flows could result in a sustainable economic upswing.

Conclusion: Modi could exit the crisis stronger than before

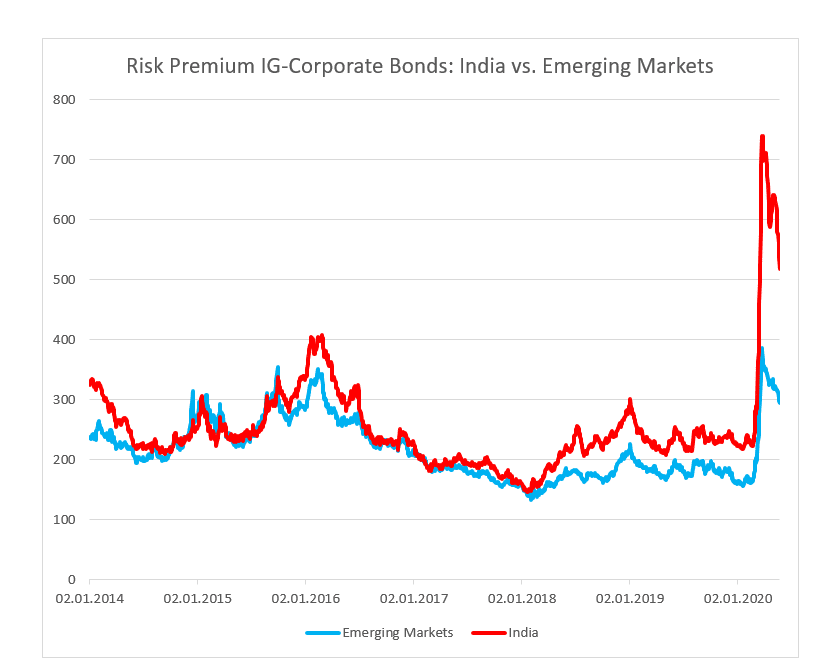

Ultimately, Narendra Modi could exit this crisis stronger than he entered it, and he might shape India in a way that the history books will remember. But does this situation offer any interesting investment opportunities? The yields of Indian corporate bonds command higher – and recently, drastically widened – spreads than the peer group with the same rating. The time to invest in some selected, individual companies may have arrived. But before we can recommend broadly-based investment, the announced reforms have to be implemented and bear fruit. Government bonds have recently widened significantly as well and are now on the level of other emerging markets.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.