After a long pause in the cycle of interest rate hikes, the central banks in the developed economies are signalling a reduction as the next change in the key-lending rate.

After the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the Riksbank in Sweden each cut their key-lending rate by 25bps in May, both the Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank are expected to ease their rates this week. By contrast, no change in rates has yet been priced in for the US Federal Reserve (Fed funds rate: 5.5%) or the Bank of England (key-lending rate: 5.25%) for June.

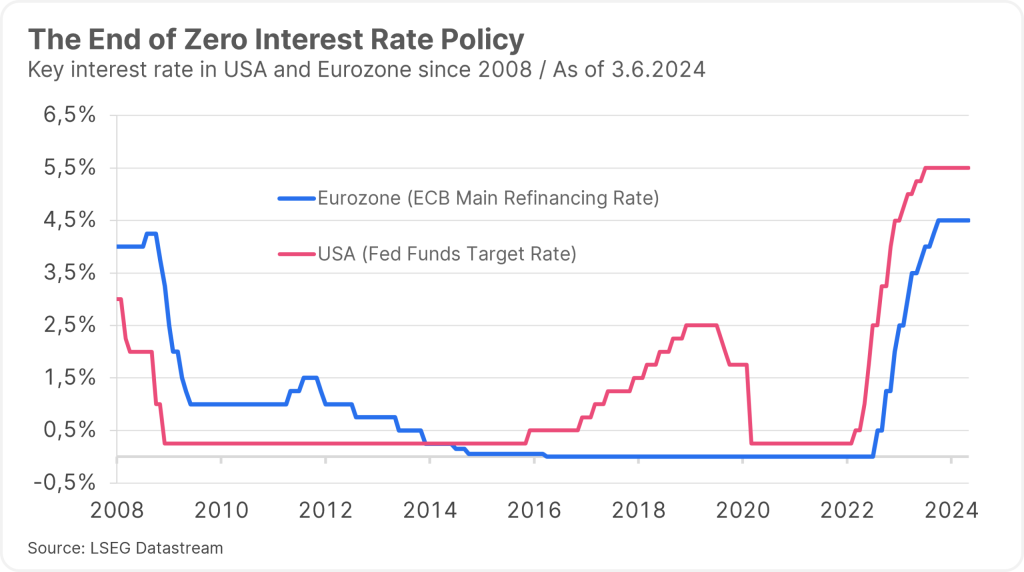

The ECB is expected to cut its key-lending rate (i.e. the so-called main refinancing rate) from 4.50 to 4.25% on Thursday. This would be the first easing of said rate for the Eurozone’s currency guardians since 2016, when the key-lending rate was cut to a low of 0%. As a result of the sharp rise in inflation, the ECB then changed its zero-interest rate policy in July 2022 and raised the rate to 4.50% in ten steps. Let us therefore take a closer look at the ECB’s interest rate policy.

Too soon or too late?

In general, central banks are faced with the challenge of having to find a sufficiently restrictive level to alleviate inflationary pressure. The risks of a misjudgement are considerable. On the one hand, cutting key-lending rates too soon could keep inflation at too high a level or even generate a second wave of inflation. On the other hand, cutting them too late could unnecessarily dampen economic activity or even cause a recession.

Recession did not materialise

The main reason for the uncertainty is the fact that the influence of central bank policy on economic growth and inflation is not quite as mechanistic as central bankers sometimes suggest. Higher key-lending rates do increase debt servicing and reduce the present value of future profits. This is because these are discounted in valuation models using the respective key-lending rate. Conversely, if it is increased, this means a reduction in the present value of these future profits.

That being said, the financial markets and economic growth have performed surprisingly well, even in the Eurozone. Historically or statistically speaking, rapid and strong key-lending rate hikes have often triggered a recession. However, the recession expected by many has not materialised to date.

In the Eurozone, gross domestic product grew by 0.3% quarter-on-quarter in Q1 2024 (1.3% annualised). The flash estimate of the purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) and the European Commission’s economic confidence report for May both point to similarly high growth in Q2. The restrictive effect of the interest rate policy is particularly evident in lending. The outstanding credit volume has been stagnating for about two years. Without credit growth, however, a sustainable return to economic growth is difficult to imagine.

Structural inflation drivers

Inflation was below the central banks’ target of around 2% before the pandemic. There are two main reasons for this:

- Globalisation

- The restrictive austerity policy in the wake of the Great Recession in 2008/2009 and the government debt crisis in the Eurozone

Both factors have been in reverse for several years, as evidenced by the trade conflict between the USA and China and the persistently high budget deficits. Both have an inflationary effect, i.e. cause inflation to rise.

Low productivity

The after-effects of the pandemic are still being felt across many levels. One of the special features is the low productivity growth, particularly in the Eurozone. In Q1, employment and GDP growth were the same at 0.3% q/q each. Also, the unemployment rate hit a new low of 6.4% in April, although GDP had stagnated for five consecutive quarters prior to the growth in Q1 2024.

However, without an increase in productivity, it will be difficult to bring inflation to the central bank’s target of 2% in the medium term, as growth in unit labour costs will then remain high. In Germany, wage growth (compensation per hour) was 6.4% y/y in Q1, while productivity (real GDP per hour) fell both year-on-year (-0.4%) and quarter-on-quarter (-0.8%). This kept growth in unit labour costs high, both year-on-year (6.8% = 6.4% wage plus 0.4% productivity) and quarter-on-quarter (1.5% = 0.7% wage + 0.8% productivity).

In order to be in line with the inflation target of 2%, wage growth would have to fall to 3% in the Eurozone, for example, while productivity growth would have to increase from 0% to 1%. However, contrary to expectations, an important indicator for wage development (negotiated wages) in the Eurozone showed an increase in wage growth in the first quarter (Q1 2024; 4.7% year-on-year; Q4 2023: 4.5%).

High inflation in the service sector

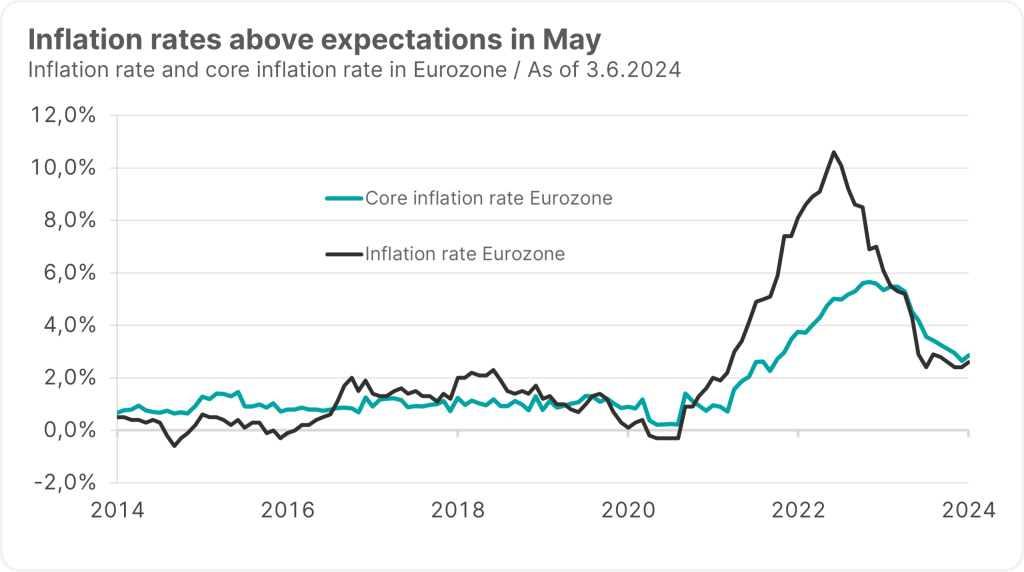

The flash estimate for consumer price inflation in May exceeded expectations. Inflation rose from 2.4% to 2.6% y/y. The core rate, which excludes the particularly volatile components of food and energy, rose from 2.7% to 2.9%.

Much like in other countries, inflation in the services sector exceeds inflation in the goods sector (just above zero per cent) and also shows little sign of falling (as indeed it increased from 3.7% to 4.1% in May).

Conclusion: interest rate level should remain restrictive

The European Central Bank has been hinting at a key-lending rate cut in June for months. Why this date has been mentioned, although strictly speaking it contradicts the data-dependent approach, remains a mystery.

The progress made in reducing inflation and the dampening effect of interest rate policy on growth are probably the arguments that will be used in favour of the rate cut. After all, inflation has fallen significantly from its high in October 2022 (10.6%), and lending has stagnated. However, a restrictive interest rate level is likely to remain necessary for the sustainable achievement of the inflation target in the medium term, as are optimistic assumptions regarding the development of the supply side (productivity), fiscal policy (consolidation), and geopolitics (trade conflicts).

The ECB announcement, including the macroeconomic projections and President Lagarde’s press conference, may provide information on the timing of further interest rate cuts. As long as the Eurozone is spared a recession, a rapid cycle of interest rate cuts will be difficult to pull off, at least as long as inflation in the service sector remains persistently high. The market reflects a reduction in the key-lending rate by a total of 0.5 percentage points by the end of the year.

No Posts Found

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.