The parliamentary election in India will begin in the coming days. A total of 970 million people will be called upon to cast their votes in the world’s most populous country (India is now just ahead of China with around 1.4 billion inhabitants) and the world’s largest democracy.

Lengthy election phase

The election will be held in a total of 7 phases over 44 days. The long duration is justified by logistical and security requirements (elections were held in 39 days in 2019). The opposition critically notes in this regard that an (overly) long election period tends to benefit the incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), as they have a well-filled campaign budget and better access to the media and can act accordingly.

Prime Minister Modi in favorite position

In general, a clear victory for the BJP and its allies is predicted. In 2019, the alliance won 350 out of 543 seats; current forecasts predict further gains and expect a total of 370 – 400 parliamentary seats. Anything other than a third term in office for Prime Minister Modi would therefore be a huge surprise.

Despite these signs, alarming events have recently been observed during the election campaign: There have been complaints of intimidation of the opposition, particularly through arrests (including that of well-known opposition leader Rvind Kejriwal). In addition, the authorities also intervened negatively in the election campaign and, for example, froze the accounts of several opposition parties on questionable grounds.

Note: Past developments and forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future developments.

Increasing tensions in the country

But even before that, the Prime Minister had already acted on several levels outside of the much-praised reform processes in order to create an atmosphere for his party and himself. Among other things, people of Hindu faith have recently been given preference in immigration (especially over Muslims).

Additional tension between the religions has arisen due to the permission that several mosques must also be opened for Hindu prayers. The nationalist orientation of the BJP’s politics is clearly reflected here. Observers believe that tensions arising in this way are accepted politically in order to unite the core electorate.

More initiative in the fight against poverty – but not without calculation

A change in focus has also been evident in the fight against poverty in the years since 2019: since then, free benefits (food) and subsidies (housing, petrol) have been significantly increased. After social spending remained stable, there was a redistribution within the department. This is very positive for those affected, but unfortunately Modi links this aid to his party and himself by being printed on the grain donations, among other things. He thus appears as an omnipresent figure and tries to expand his influence within the state.

As popular as Narendra Modi undoubtedly is nationally, his actions are now being viewed critically abroad. The desire of many Western companies to find a more stable location compared to China is unfortunately being undermined somewhat as a result. Geopolitically, India is also not quite in the position it could be in (positioning itself as a strong counterweight or alternative to China) due to its current Russia-friendly policy.

Conclusion: hope for a return to a pro-Western course

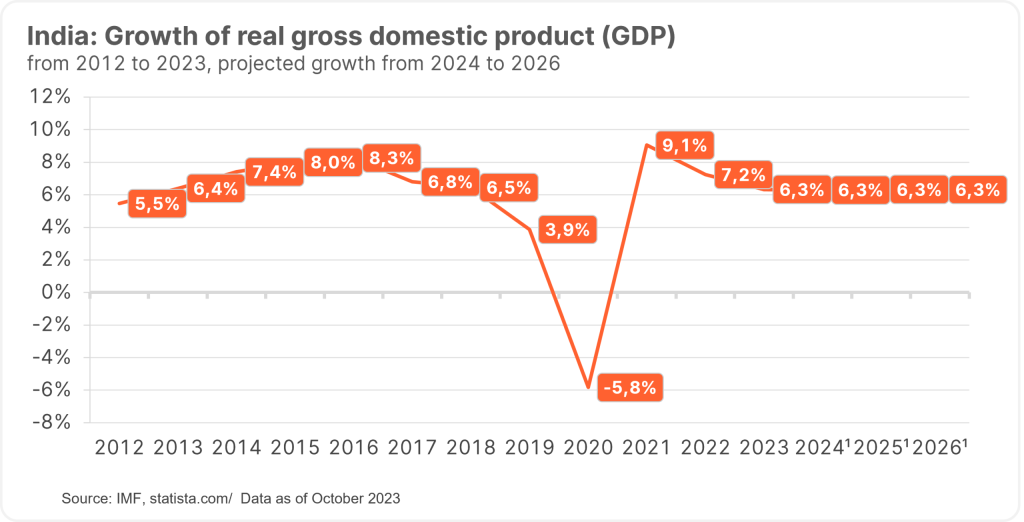

It remains to be hoped that a pro-Western course will return to the fore after the elections. After all, India’s macroeconomic development can be described as very positive – last year, the country recorded the highest GDP growth among the relevant economies worldwide.

For the years 2024 and 2025, the OECD and the World Bank also expect the highest growth in India with rates of over 6% each (China is pushed into third place by Indonesia).

Note: Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.