Last week on Wednesday, the S&P 500 lost more than 3%, followed by another loss of more than 2% on Thursday. These were the last two in a series of down moves – six days in a row – that left the main US index 6.7% below its previous peak.

Corrections like this one do not happen too often but they are not super-rare either, and they are not necessarily a signal of a fundamental change in the market backdrop. The last time that markets experienced a drop of this magnitude – a fall of more than 5% over the course of three days – was in February this year, and before that we saw similar down moves in January 2016 and August 2015. None of these events was significant enough to derail the bull-market for more than a couple of weeks.

Of course, the rebound on Friday does not mean that the troubles are over. In fact, it would be surprising if normalcy were to return only a couple of days after volatility doubled. In 2015, 2016 and earlier this year it took two months or more before volatility reapproached pre-corrections levels.

The correction triggered a lot of commentary[1], which is no surprise given the fact that the current bull market is already in its 9th year and there is no shortage of risks that could bring it to an end.

There are two obvious questions:

- What caused the meltdown?

- And more importantly, what can we expect going forward?

No obvious trigger

There is no shortage of culprits for last week’s correction: the steep rise in US bond yields; the anticipated slowdown in global economic growth; trade tensions; the removal of the Fed’s (liquidity) “punch bowl”; stretched valuations; and President Trump’s attack on the Fed. However, none of the explanations that have been put forward is fully convincing.

Yes, US 10 year treasury yields jumped by 17 basis points in the first week of October, which may have put a strain on equity investors, but yields also had climbed 20 basis points in the first three weeks of September without preventing the S&P 500 from reaching its all-time high on September 20. It is also worth noting that two largely contradictory stories have been circulating regarding the negative impact of interest rates: until recently, pundits were concerned about the flattening of the US yield curve because it was seen as a bellwether of a coming recession, whereas now some commentators see rising long-term rates and a steepening yield curve as the main trigger for last week’s correction.

And for the other explanations: slowing (but still solid) global growth, President Trump’s trade policies, and the Fed’s policy intentions have been known for some time and are, therefore, not rally plausible explanations for last week’s meltdown. As Barry Ritholtz, a Bloomberg columnist and investor, has pointed out[2], many of the alleged causes for the correction are simply ex-post explanations of what are basically unpredictable short-term market movements resembling more a random walk than anything else.

The beginning of the end?

Probably not – although headwinds are getting stronger.

As mentioned before, there is a long list of risks, which – if they materialized – have the potential to derail global equity markets. The US-Chinese trade war; a strengthening of centrifugal forces in Europe in response to a mishandled Brexit or Italian budget woes; slower Chinese growth, monetary policy errors in the US or elsewhere; emerging market blow-ups; surging crude prices – to just name the most obvious challenges. Every single event/development one on this list could trigger a slowdown in global economic growth, rising uncertainty and growing risk aversion.

That said, a number of factors still suggest that the fundamental backdrop for stocks will remain constructive for some more time. Most importantly the likelihood of a US recession during the next twelve months – the single most dangerous threat to US equities – remains low. The New York Fed “probability-of-a-recession” indicator is below 15% (although it has moderately risen as of late). According to a recent survey among US business economists, 56% of respondents see the US moving into a recession in 2020 and 33% in 2021 or later[3]. The recent data flow has been broadly in line with these forecasts, implying that the biggest threat for US and, therefore, global equities remains only a remote possibility that should not prevent a further leg up.

Second: Consensus forecasts for 2018 and 2019 point to solid earnings growth across developed markets. According to consensus data compiled by Factset, global earnings are anticipated to grow by 10% in 2018 and by 12% in 2019. And similar to last year (and in contrast to 2014-16) forecasts have been revised up during the course of the year. In the US, the main trigger, of course, was tax reform but positive revisions continued in the 2nd and 3rd quarter.

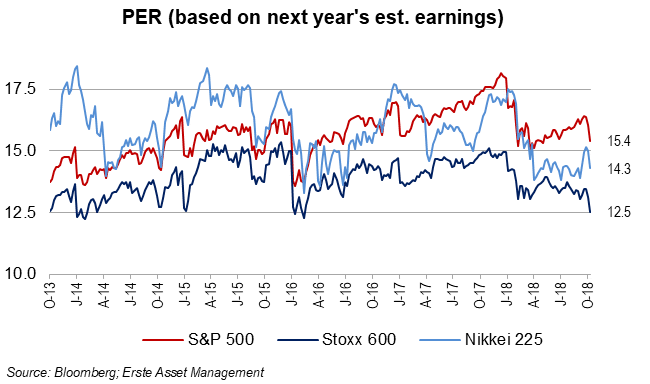

Third: Due to the solid earnings outlook, valuation has become less of a risk. In an earlier blog this year[4] I made the claim that investors should not count on a multiple expansion in 2018. In fact, equities have derated in the course of the year. As a result, according to Bloomberg data, the 2019 earnings multiple in the US is 15.4x, in Europe 12.5x and in Japan 14.3x, all of which do not look demanding.

Finally: The recent rise in US long-term yields may even be a positive signal because it suggests that investors have turned more positive on the longer-term growth outlook for the US – which ultimately is positive for equities[5], as long as the Fed does not make any policy mistakes.

Bottom line

Last week’s meltdown was a reminder, if one was needed, that stock price movements are not following a one-way street. The number of daily down moves of more than 1% has increased in 2018, which is a signal that investors have turned more nervous. However, while serious risks are looming (as always, one should add), nothing has changed fundamentally over the past few weeks that would require a complete or even partial overhaul of our view of the world in general and stock markets in particular. Of course, the main risks need to be closely monitored and portfolios need to adjust in accordance with incoming data such as the upcoming quarterly earnings and company guidance news but in itself the correction does not justify a move out of equities.

Disclaimer:

Forecasts are not a reliable indicator for future developments.

[1] Wigglesworth, R., “What is behind the global stock market sell-off?”, https://www.ft.com/content/af34550e-cd01-11e8-b276-b9069bde0956 , Oct 11, 2018

El-Erian, M.A., “How to Think About the Market Sell-Off”, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-10-10/u-s-stocks-and-bonds-fed-pullback-contributed-to-market-plunge , Oct 11, 2018

Mackintosh, J., “Is It Time to Buy the Dip?”, https://www.wsj.com/articles/is-it-time-to-buy-the-dip-1539266570, Oct 11, 2018

FT Editorial, “The long bull market enters its twilight period” https://www.ft.com/content/9ed80a84-ce0a-11e8-b276-b9069bde0956, Oct 12, 2018.

[2] Ritholtz, B., “The Stock-Market Meltdown That Everyone Saw Coming”, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-10-11/the-stock-market-meltdown-that-everyone-saw-coming, Oct. 11, 2018.

[3] Kearns, J., Two-Thirds of U.S. Business Economists See Recession by End-2020”, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-01/two-thirds-of-u-s-business-economists-see-recession-by-end-2020, Oct.1, 2018.

[4] Szopo, P., Global equities: Five charts on where we stand“; https://blog.en.erste-am.com/global-equities-five-charts-stand/ , Jan 29, 2018.

[5] Irwin, N, “Interest Rates Are Rising for All the Right Reasons”, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/upshot/interest-rates-are-rising-thats-great-news-for-most.html , Oct 11.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.