The G20 summit had a difficult start at the end of June: The US and China officially put their trade negotiations on hold, the conflict over the nuclear agreement with Iran escalated again, and many questions regarding the Brexit remained unresolved. Rarely has the group of the 20 most important industrial nations, and by extension the world economy, had to face so many serious challenges simultaneously. Investors were not the only ones to look forward to the meeting’s start in Osaka, Japan.

Pleasant surprise in a tense environment

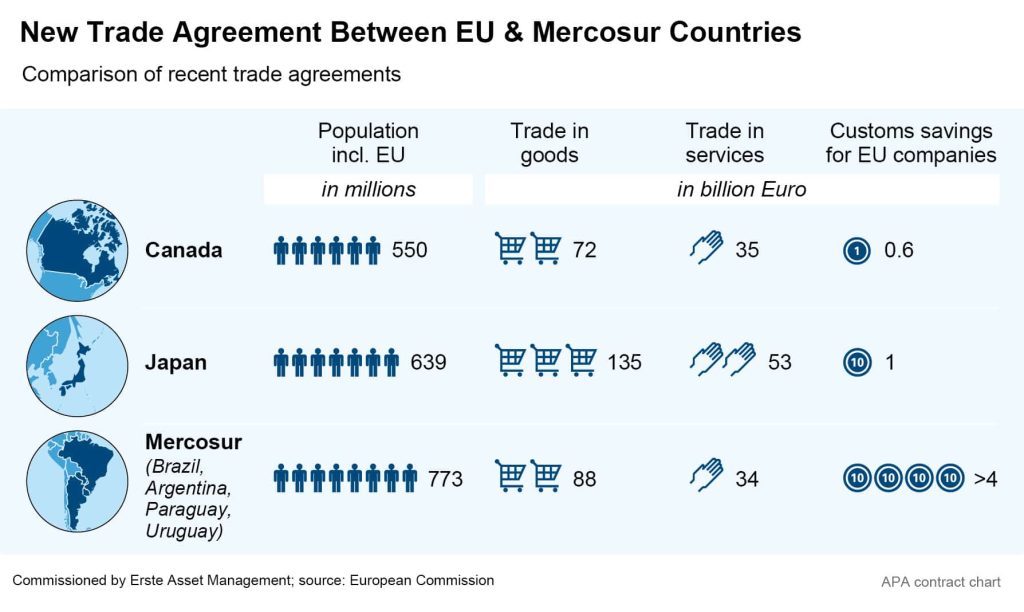

The weekend did indeed start with a breakthrough, but the good news came from an unexpected direction – not Japan, but rather Brussels and Buenos Aires: The European Union and the South American trade bloc Mercosur announced the formation of the world’s largest free trade zone. After 20 years of negotiations, a political agreement on abolishing tariffs and other trade barriers has been reached. Outgoing EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker spoke of a “historic moment”.

The agreement between the EU and Mercosur countries Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay is intended to strengthen the exchange of goods and save companies billions. The EU Commission estimates that the agreed treaty will save European companies EUR 4bn in customs duties.

Potential in commodity and capital markets

According to the Commission’s data, exports by EU companies to the four Mercosur countries amounted to around EUR 45bn in 2018, while exports in the other direction amounted to EUR 42.6bn. The EU is already the main trading and investment partner for Latin American countries. Mercosur mainly exports food, beverages and tobacco to the EU. From there, machines, transport equipment, chemicals and pharmaceutical products are exported to Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. The two regions also engage in lively trade on the capital market: the cumulative volume of capital from the EU increased from EUR 130bn in 2000 to EUR 381bn in 2017. Conversely, in 2017 investors from the Mercosur states held investments to the tune of EUR 52bn in the EU.

Further steps and scepticism

Shortly after the “historical” agreement was published, resistance to it began to take shape. While sectors such as the automotive industry were satisfied with the planned changes, other industries such as farmers fear increased competition from beef, poultry and sugar from South America. With its less strict regulations for environmental protection, crop protection and the use of antibiotics, consumer protection agencies and environmentalists were quick to object: “France is currently not prepared to ratify the agreement,” a government spokeswoman said on the French radio last week. Before the agreement can be put into effect, all EU member states as well as the EU Parliament, among others, must approve it, which will most likely require renegotiations and additional agreements in some areas. Seen thusly, the largest free trade zone in the world has not yet reached its goal. However, the milestone of the agreement can be considered a positive signal in a conflict-laden environment.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.