Recently, economic indicators have provided evidence of resilience of economic growth to multiple headwinds but, unfortunately, also uncomfortably high core inflation rates despite declining trends in producer prices as well as inflation expectations. The central banks could now pursue an even more restrictive monetary policy. Will they be lucky and achieve their goals?

Growth resilience

The purchasing managers’ indices for June are in line in the aggregate with moderate growth in the global economy around potential. However, the global index fell month-on-month for the first time in seven months. This represents a weak signal of slowing economic momentum. The global purchasing managers’ index for the manufacturing sector continued its falling trend. The subcomponents suggest a slight contraction in production, with the ratio of new orders to inventories providing no indication of stabilization. The global purchasing managers’ index for the services sector remained well within the growth range, even though it fell compared with the previous month. Indeed, catch-up demand in the service sector following the COVID-induced opening measures was a key supportive element for economic growth. However, as catch-up demand becomes more saturated, its contribution to overall economic growth also declines. On a positive note, the price components of the purchasing managers’ indices suggest that price pressure is easing.

Gradual slowdown

The U.S. labor market reports for the month of June point to another very strong and tight labor market. The unemployment rate remained at a very low level of 3.6%. Employment growth remained high, but shows a declining trend. Strikingly, growth was lower in the private sector (149 thousand) than in the total nonfarm sector (209 thousand). However, growth in average weekly earnings, at 0.4% month-on-month and 4.4% year-on-year, showed no evidence of decline.

Inflation Persistence

The focus of interest this week is the release of U.S. consumer price inflation for the month of June. Estimates show only a slight decline in overall inflation, excluding the traditionally volatile components of food and energy, from 0.4% month-on-month in May to a still uncomfortably high gain of 0.3%. On an annual basis, core inflation would then continue the falling trend, from 5.3% in May to 5.0%. The central bank will pay particular attention to core inflation in the services sector excluding rental prices. This fell to just 0.16% month-on-month in May. This is even below the average of 0.19% for the period from 2012 to 2019.

Higher for longer

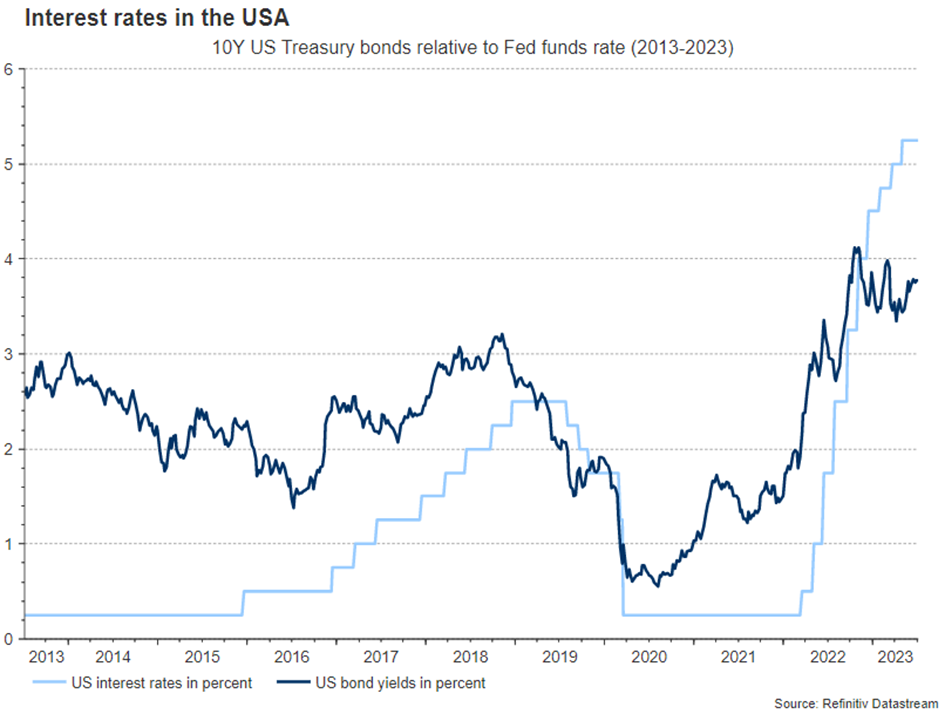

The only slow decline in inflation is motivating central banks to pursue an even more restrictive monetary policy. This means not only further key rate hikes, but also holding the higher key rate level for a longer period, say the next twelve months. This is all the more true as the labor market in advanced economies remains very tight. In fact, market prices show a further increase in key rate hike expectations. By the end of the year, plus 0.3 percentage points in the U.S. and plus 0.5 percentage points in the euro zone are priced in. A key rate hike in Canada is expected on July 12, from 4.75% to 5.0%. Even though the unemployment rate in Canada rose for the second time in a row in June (to 5.4%, April: 5.0%), employment growth was exceptionally strong at just under 60 thousand.

Lower risk of recession

In addition, expectations for key rate cuts have diminished after interest rates have peaked. The timing has been pushed further into the future, and the magnitude has declined. There are two reasons for this. First, the hints for continued economic growth (with downside risks) implies a rather low probability of an immediate “real” recession in the advanced economies. This is in contrast to a stagnation or “technical” recession, defined as a decline in real economic growth for two quarters in a row. In the absence of a recession, central banks are also less likely to cut key interest rates. In addition, inflation could fall further but anchor itself above the central bank target of 2%. This also implies a higher policy rate in the long run, unless central banks abandon the inflation target, either explicitly or covertly. At the very least, this can explain why the rise in U.S. Treasury yields since early July (from 4.37% to 4.55%) has paralleled the rise in inflation-adjusted yields (from 2.09% to 2.27%).

For a glossary of technical terms, please visit this link: Fund Glossary | Erste Asset Management

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.