Following last week’s surprisingly strong employment report, the odds that the US Federal Bank will start raising its policy rate at the next FOMC-meeting in December jumped to almost 70%. Of course, 70% is still short of 100%, but most observers believe that something terrible must happen in the next four weeks to make the Fed reconsider, particularly in light of President Yellen’s statement in September that the FOMC’s thinking suggests a “call for a funds rate increase later this year”.

While the case for starting the lift-off remains a close call as Kenneth Rogoff pointed out, it has strengthened in recent weeks as US economic data have turned more positive relative to expectations, according to Citi’s economic surprise index. Most importantly, the improvement in the job market is continuing. The US economy has been adding, on average, 200,000 jobs in the non-farm sector each month in 2015.

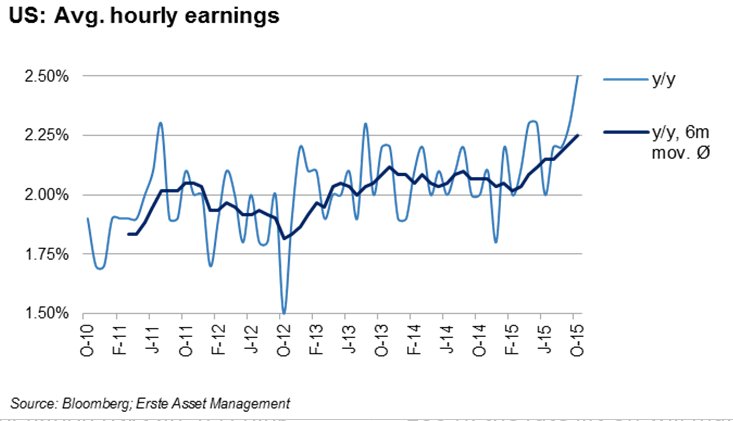

The unemployment rate dropped to 5% and there are signs that the Phillips-curve is doing its job, finally. Average hourly earnings are now growing at an annual rate well above 2%. This may still not be exactly the “whites of inflation’s eyes”, which Paul Krugman wants to see before any rate hike, but it is a sign that deflation risks are receding.

The possible fallout from a December lift-off has been a big issue in the financial press and the international blogosphere, as well as in the minds of the policy makers themselves. However, it is far from obvious that an increase of the Fed Funds Rate by 25 basis points – and nothing else is realistic – in December would have serious repercussions: As mentioned before, there has probably never been a monetary measure that was publicly discussed in more depth than the Fed’s next interest rate move. The surprise effect should be very benign.

Second: The link between policy and market rates is weak, with the sign depending on the circumstances. Based on previous examples (1994, 1999, 2004), the rate lift-off will mainly affect the short end of the yield curve, while the impact on long-term rates – which are more relevant for the real sector – and on interest rates outside the US will probably be limited. In any case, we will most likely see some curve flattening following after the Fed’s move.

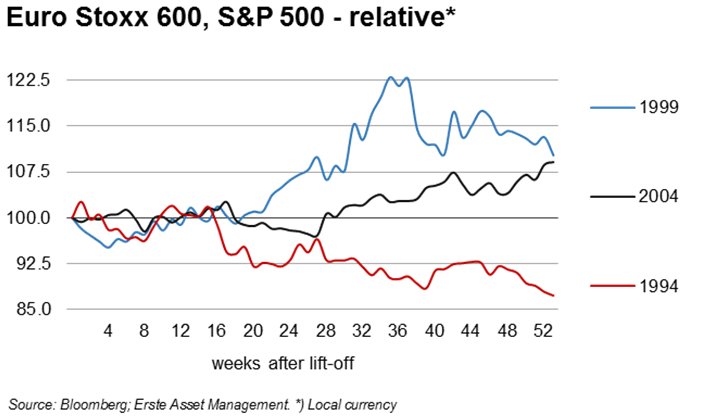

Third: The performance of equity markets during previous periods of rising rates does not suggest that rate lift-offs are followed by lasting bear markets.

For example, in 1999 and 2004, both US and European stock indices – after minor losses in the first months immediately after the event – posted significant gains during the twelve months following the Fed’s first rate move. It is also noteworthy, that there is no strong pattern regarding the relative performance of US and European equities after US rates were starting to move upwards.

Fourth: From a US perspective, one of the main fears is that the possible rate hike will lead to further dollar strengthening, which in turn may threaten US economic growth. In addition, emerging economies with high foreign debt may suffer. However, the chart below shows that in the previous three cases of rate lift-offs this has not happened.

In fact, the US currency started strengthening 4-6 months before the rate hike and softened after the fact. Of course, this time it may be different considering that major central banks outside the US maintain or consider even extending a policy of monetary easing. That said, the USD spot index (Bloomberg: DXY) already gained 25% since mid-2014 and the real trade-weighted dollar index is at its highest level since 2005. The dollar’s further upside, therefore, might be limited (although it is worth remembering that exchange rates are notorious for overshooting).

No reason to get scared

The main message from looking at previous experiences is that the response of financial markets to the lift-off in December will likely be less dramatic than widely expected. More important than the timing of the first move itself will be which signals the Fed will be sending out with regard to the path of interest rates during 2016 and beyond. President Yellen already stated that the ‘normalization’ – a term requiring a separate discussion – will be take longer and will be less steep than during previous periods when rates were hiked. Currently the market expects a very moderate increase in the Fed Funds Rate until the end of 2016 (to around 1%). Any indications that the Fed would move more aggressively would be taken negatively (as long as the growth outlook remains broadly unchanged),whereas any signals that rates will not be raised at all in the foreseeable future will probably confirm expectations that the world is moving towards deflation.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.