The change in expectations for future key interest rates continues to be the most important determinant of market prices. Almost two weeks ago, the liquidity crisis in British government bonds led to a rise in various stress indicators for the entire financial system. As a result, expectations for future key interest rates in the developed economies fell temporarily. This trend was reinforced by market commentary regarding an imminent reversal (pivot) of central bank policies toward a somewhat more cautious approach. However, these hopes were quickly dashed. Market prices for future key interest rates have risen once again in recent days, putting renewed pressure on the markets.

Good employment growth

As the most important central bank, monetary policy at the US Federal Reserve is in the spotlight. Indicators released last week – particularly US labor market data – suggest it is far too early for a pivot. In the month of September, nonfarm payrolls increased by 263,000, and while over the course of the year the growth in new employment has trended downward (high: 714,000 in February), the September reading is still far from a recession. Working assumption: As long as employment growth remains above a level of 100,000, the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will not be swayed from their restrictive stance in the current environment, which is geared toward fighting inflation.

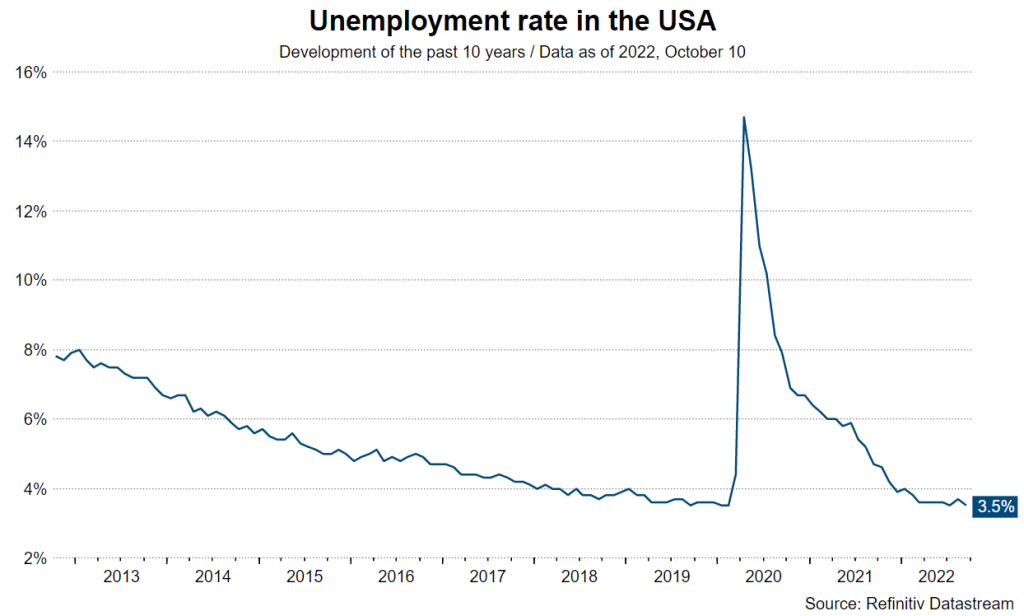

Very low unemployment rate

Other indicators confirm this assumption. Unemployment rates were at a very low level in September at 3.5% of the labor force (sum of unemployed and employed). The Congressional Budget Office estimates the “natural” rate of unemployment at 4.4%. This means that below this level there is an increased risk of wage inflation (Phillips curve). Currently, most countries are facing first-round effects at the inflation level. The sharp rise in energy prices is being passed on to numerous other product prices. There is little central banks can do about this.

However, they can try to contain the two-round effects. Here, the focus is on the labor market. Excessive wage increases could set off a wage-price spiral. The central banks, including the Fed, are now trying to cool down (damage) the labor market with a restrictive stance to such an extent that a price spiral is prevented. In the past, however, the unemployment rate has risen sharply, not just slightly, in such an environment. The formula is: high inflation and a low unemployment rate mean high recession risks if, at the same time, central bank policy is restrictive.

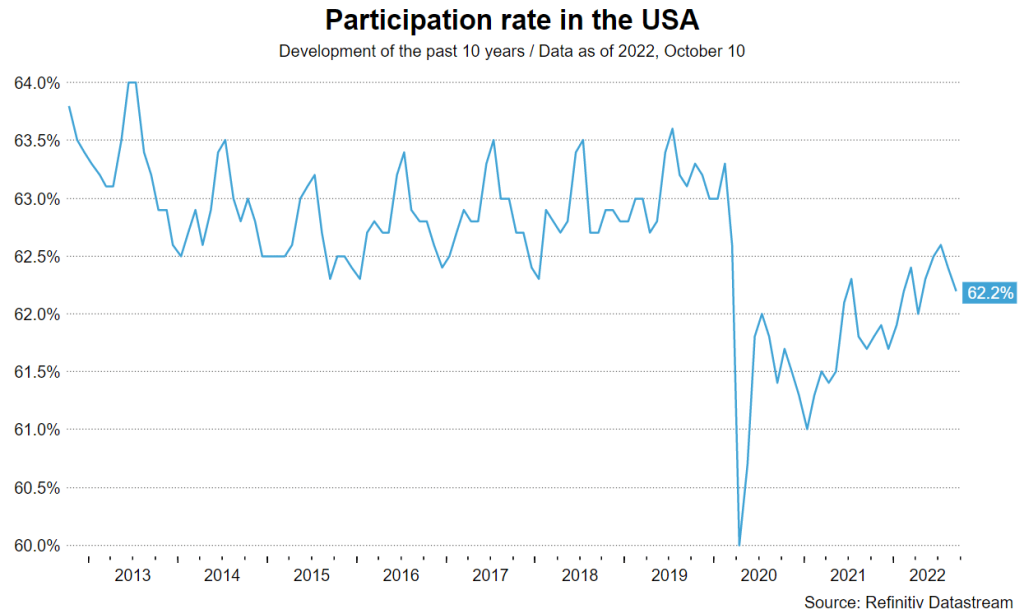

Low participation rate

For the US, there is the special case that the participation rate, which is the share of the unemployed and employed (the labor force) in the working-age population, is low. The further development of this indicator will have a significant impact on the Fed’s monetary policy and recession risks. Overall, the participation rate shows an upward trend after the plunge in spring 2020 (April 2020: 60.2%). The hope is that the trend will continue and soon reach pre-pandemic levels (February 2020: 63.4%).

If more people start participating in the labor market again, the still very high demand for labor could be met more easily. The very tight labor market would ease somewhat, the risk of a wage-price spiral would decrease, and the Fed would not have to raise key interest rates so aggressively. This would increase the likelihood of a “soft” landing (low economic growth but no recession). However, the participation rate (the supply) fell slightly in the month of September (62,2% after 62.4%). This indicator is also unlikely to have appeased Fed members.

Significant decline in vacancies

On the other hand, demand has also fallen. In the month of August, job vacancies amounted to 10.05 million, compared to 11.17 million in the previous month. The ten percent decrease means a lower ratio between vacancies and unemployed persons (1.67 instead of 1.98 before). The Beveridge curve thus suggests that the labor market is still very tight, but not as tight as the month before. At least this development can be used as an argument for lower secondary round effects and thus less restrictive Fed policy. Establishing a falling trend in job vacancies would help ease the labor market. Especially if the participation rate rises at the same time.

Key interest rate hikes despite rising stress indicators

As long as job growth remains strong and unemployment and participation rates remain low, the Fed will maintain its basic restrictive stance. Signs of a decline in demand for job vacancies help, but are not (yet) decisive. Of course, the Fed is also watching the tightening financial environment and the deterioration of many liquidity indicators. However, as long as the deterioration is seen as non-systemic, the Fed (and will the other central bank) will stay on course to fight inflation. Postscript: This, however, reinforces the feedback loop from the deteriorating market environment to the economy and central bank policy, making a somewhat more cautious approach by the Fed more likely after all.

For a glossary of technical terms, please visit this link: Fund Glossary | Erste Asset Management

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.