The European Central Bank (ECB) intends to buy bonds despite the recent ruling of the German Constitutional Court. Early last week, the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe ruled that the ECB’s billion-euro bond purchase programmes partly violated the constitution, and in doing so, opposed a ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that deemed the bond purchases legal in December 2018.

The ECB central bankers have so far been unperturbed by the ruling. As an independent institution, the ECB is accountable to the European Parliament and driven by its mandate, said ECB President Christine Lagarde on Thursday at a conference held by the news agency Bloomberg.

“We will continue to do whatever is necessary to fulfil this mandate,” she said. ECB Vice-President Luis de Guindos said, “We remain more determined than ever to ensure supportive financial conditions across all sectors and countries to allow this unprecedented shock to be absorbed.”

ECB has already invested EUR 2.6tn in securities purchases since 2015

Between 2015 and 2018, the ECB had invested around EUR 2.6tn euros in government bonds and other securities – most of it through its Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), to which the judgment refers. In November 2019 the purchases were relaunched, initially comprising a comparatively small amount of EUR 20bn per month.

With the bond purchases, the ECB wants to prevent possible deflation after its interest rate cuts had not had sufficient effect. In technical jargon this is called quantitative easing (QE).

Central banks normally try to achieve monetary policy goals, such as monetary stability or economic growth, by controlling their key interest rates. After the financial crisis, however, many central banks lowered their key rates to virtually zero, exhausting this measure. In this case, central banks can fall back on unconventional measures such as “helicopter money” or even bond purchases.

Other central banks already chose this path before the ECB, the pioneer being the Japanese central bank, which launched a bond purchase program in 2001 to combat deflation in the country. In 2008, the US Federal Reserve announced a massive bond purchase program to fight the financial crisis, after having already lowered its key interest rate to zero.

Since 2009, the British central bank has also been buying bonds.

Under these programs, the central banks buy up private or public securities, such as government bonds, from the commercial banks. These purchases increase the banks’ monetary base and liquidity, while at the same time lowering the interest rate level in the bond market.

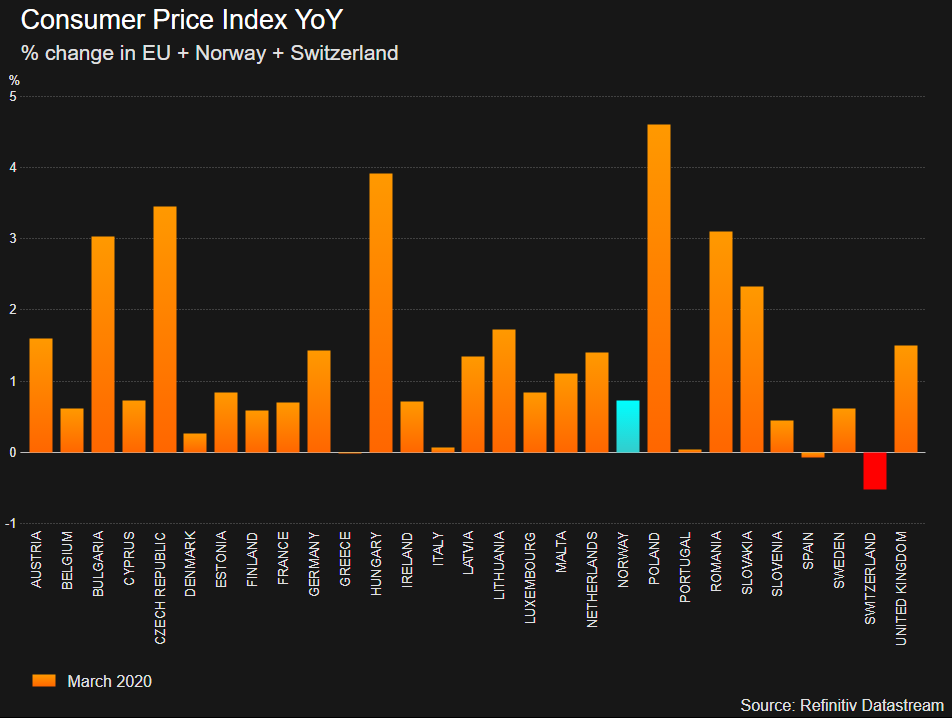

This is intended to boost credit demand, investment activity and private consumption, but also to combat too-low inflation. Through its purchasing program, the ECB is also trying to achieve its inflation target of approximately two per cent; however, it is currently far from achieving this: consumer price inflation in the euro zone recently lay at 0.4 per cent, and in view of the coronavirus crisis the ECB is preparing for a further decline.

Purchases aren’t forbidden state financing, but not conducting review is unconstitutional, Court rules

Critics of bond purchase programmes often argue that this could be a covert form of government financing. In 2017, the German Constitutional Court had already inquired of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) whether the ECB’s bond purchases constituted a prohibited form of public financing.

In its much-publicized ruling, however, the ECJ had declared the purchases to be lawful. The constitutional law experts in Karlsruhe have also “acquitted” the ECB in their recent ruling on this point. However, it is in violation of the constitution that the ECB did not review the proportionality of its measures.

It should also have examined the economic consequences for savers, shareholders and property prices, the ruling states.

The Governing Council of the ECB must now demonstrate that the purchase programme is proportionate within three months, as otherwise, the Deutsche Bundesbank is prohibited from participating in the programme after a transitional period of no more than three months. The Bundesbank is the ECB’s largest shareholder, owning a share of more than 26 per cent, and its purchase volume is correspondingly large.

As a consequence of the ruling, the Deutsche Bundestag should by law request information on ECB activities from the Bundesbank, states a proposal in a confidential legal analysis by the Bundestag made available to Reuters.

The paper states that the Bundestag should examine the proportionality of the ECB’s bond purchases and continuously be informed about the purchase programme. In addition, the proportionality of the purchase programmes must be reviewed at regular intervals.

The Bundestag’s lawyers for European affairs do not expect the ruling to have a major impact on the PSPP bond purchase programme to which it refers. Analysts also expect that the ECB will prove the proportionality and continue the PSPP bond purchases.

Purchase limits could affect pandemic emergency programme

If the judgement were to refer to the EUR 750bn pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP) of the ECB launched this year, this could exacerbate the matter: According to the ruling, the ban on public financing only applies if the ECB’s share in a government bond does not exceed 33 per cent and the ECB distributes its purchases among the individual countries according to the share of local central banks in the ECB’s capital.

However, it is precisely these purchase limits and allocation keys that are handled flexibly under the new PEPP bond purchase program, which is bound to tie the ECB’s hands to a certain degree and limit its scope for action.

The ECB could now point out that the pandemic programme is not covered by the ruling, or it could also comply with the limits and key values in this regard as well. In any case, analysts expect the ECB to firmly adhere to its PEPP crisis programme.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.