The world is in a state of emergency, with the corona pandemic constituting a global health, economic, and financial crisis. The term “Coronacession” has been created as a chimaera of corona and recession.

The central question is how deep the emergency runs and how long it will last. The speed of the development is breath-taking. Yesterday’s pessimistic scenarios are today’s optimistic ones. This environment has had a clearly negative impact on the financial market.

What about the health system?

The high growth rate of the confirmed new infections outside of Asia is worrisome. The issue is, among other things, that about five percent of cases need intensive care at a hospital. If too many severe cases start inundating too few hospital beds, people will be dying at higher rates.

In order to avoid overburdening the healthcare system, many governments have put drastic containment measures such as lockdowns in place. The term of the moment is “social distancing”.

How extensive and how long the social isolation measures have to be maintained depends on a number of factors:

- how significantly can the growth rate be slowed down? When will medication be available?

- When will a sufficient number of test kits, protective suits, and hospital beds be available?

- When will the contact tracing process be at adequate levels?

Much like the proverbial medal with its two sides, the isolation measures on the one hand contain the virus, but on the other hand they directly translate into the partial disintegration of the GDP. The GDP is the sum of all the goods and services produced within a certain period of time, measured in a certain currency.

What are secondary round effects?

If nobody is staying at hotels, taking flights, or eating out, there are no transactions that would contribute to the GDP. This clearly shows that the GDP does not top the list of priorities as far – as the quality of life is concerned. Healthcare trumps material welfare.

… – or it does so at least for a while, because the effects on the economy are dramatic. The estimates vary, but GDP may experience a 5 to 10% slump within a period of three months, depending on the country.

While this is significant, it is still not the core of the economic problem. The real issue are the so-called spill-over and second-round effects. Once sales have ground to a halt, a company can pay its fixed costs only so long.

Thus, a wave of bankruptcies (i.e. companies stop existing), a credit squeeze (banks stop giving loans), and an increase in unemployment rates are looming on the horizon.

Making money out of air

As dramatic as the containment measures against the virus are, as comprehensive is the support aimed at avoiding a depression (i.e. a persistent, severe recession).

The central banks around the globe cut the price of money (i.e. the key-lending rates) to zero percent, increase the money supply to dizzying heights, ensure a high level of cheap liquidity for the banks, set up purchase programmes for government and corporate bonds, and try to fight the malfunctioning of the capital market (more details below).

The most powerful weapon of a central bank is that it can create money from nothing. Of course, central banks have to be careful doing so, but in times of crises, this option has been used.

The most important function of the central bank is that of lender of last resort. When no-one else is giving loans, the central bank will step in and take over this task.

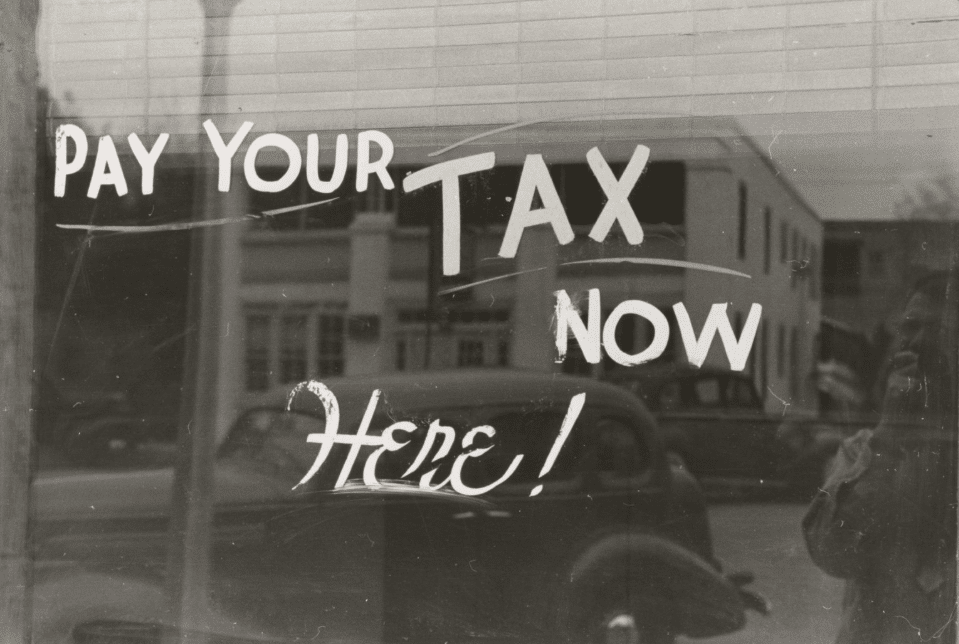

The most powerful “weapon” is tax revenue

The most powerful weapon of the Ministry of Finance (MoF) in fighting the crisis is the total volume of its tax revenues, both current and future.

Said revenues fund reduced work hours for employees, unemployment benefits, the guarantees of corporate loans or bonds, health insurance, direct help, and tax and duty respite.

The most powerful “weapon” of the ministry of finance in the fight against the crisis is the total tax revenues, current and future.

Theoretically, the MoF could also offset the slump in demand (i.e. sales) that companies experience directly, but at the moment, the help is largely of an indirect nature.

Measures aimed at fighting crises have been around for a long time. The novel aspect is the high degree of cooperation between central bank and MoF.

In some countries, the MoF partially guarantees the bonds (short-term corporate loans) that the central bank buys. The central bank buys large volumes of the bonds that have previously been issued by the state.

What is helicopter money?

The transition to the so-called helicopter money is no singularity, but a gradual development. In a perfect scenario, the central bank would transfer money directly to every citizen via the MoF.

This step is currently being discussed in the USA. There is a “by any means necessary” consensus among all the parties involved in economic policies in order to absorb the possible second-round effects.

Market participants surprised by the developments

The market participants have been taken by surprise by the developments as well. Given that the economic scenario has turned from “recovery of the global economy in 2020” to “contraction in the first half amid downside risks”, the price fluctuations were significant.

After the drastic slump on the equity and corporate bond markets, the markets now have a hefty decline in economic output in the first half priced in.

The crucial question for investment decisions is whether and when we are likely to see the economy rebound.

On top of the share price crash, the liquidity of trading has fallen drastically as well. Many securities are traded at significant premiums or discounts, respectively.

This phenomenon is well known from previous crises. The elevated uncertainty has triggered a sell-off, which reinforces the price trend even more – as do technical aspects of the market (high share of passive funds, low market depth due to regulatory requirements, quantitative signals).

The central banks have responded to this decline in liquidity on the market by putting in place comprehensive bond purchase programmes.

Exceptional environment

The current environment is unlike much we have witnessed before. It dwarfs past crises that we have seen since WWII. In order to be able to make any predictions, it is worth drawing up different scenarios.

- Scenario 1: after the slump in the first half, the economy recovers in the second half of the year. The measures taken to contain the virus are being reduced, and the ones taken to limit second-round effects have been successful.

The economy follows a V-shaped growth pattern. In this case, equities are the optimal form of investment.

- Scenario 2: the economy is recovering slowly, because the effectiveness of the economic policies is limited. The sentiment remains subdued and dampens investments, consumption, and the labour market. The recovery will only take hold in 2021. This is a U scenario, because the slump is not a gorge but a valley. This scenario suggests a mixed (i.e. broadly diversified) portfolio.

- Scenario 3: no recovery in the foreseeable future. The measures taken in an effort to contain the virus may take longer than expected, and the support may not be sufficiently effective. This is an L scenario, where the investment product of choice are credit-safe investments (i.e. government bonds).

We are likely to see an initial, noticeable relief or recovery for risky assets such as equities and corporate bonds only once the end of the containment measures is in sight and at the same time the credibility of the support measures is solid.

Our dossier on coronavirus with analyses: https://blog.en.erste-am.com/dossier/coronavirus/

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.