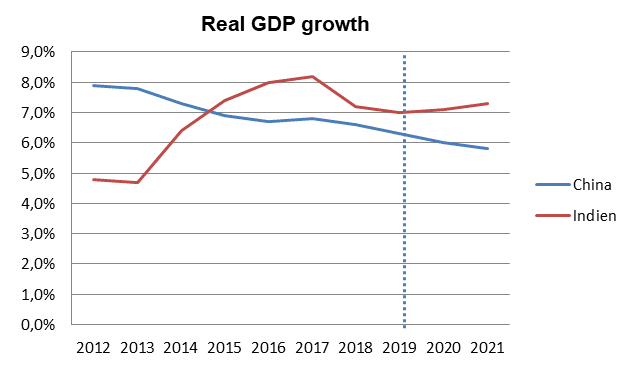

India has been one of the fastest growing economies in the world for several years. Its GDP growth numbers have been above those of the emerging markets heavy weight China since 2015. India is expected to maintain a growth rate of 7% in the coming years, whereas China seems to be heading for a decline below 6%.

Source: Bloomberg

Protagonists of the election campaign for the parliamentary election held in spring highlighted the economic expectations for the country during their campaign: the then Indian Minister of Finance forecast the rise of India to become the third-largest economy of the world by 2030 (with a GDP of about USD 10,000bn), behind the USA and China. The high expectations are attracting investors from around the globe, and the stock exchange in Mumbai is booming. But, can the economy meet the high expectations, or will India remain the “future talent” forever?

One of the biggest challenges

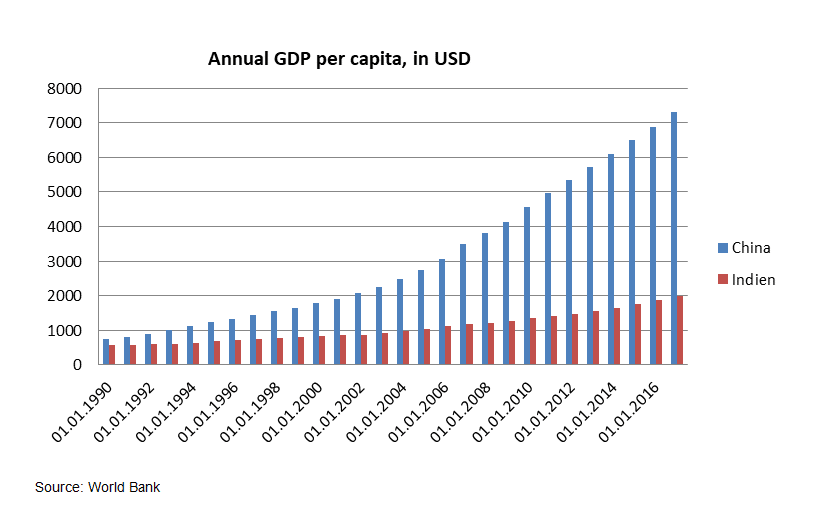

One of India’s biggest challenges is the creation of an advantageous economic framework. Historically speaking, the federal state structure has led to a broad array of different frameworks, with every State having its own set of laws and economic policies. This divergence in legal systems in connection with the overregulation of the private sector and excessive bureaucracy have discouraged investors. China, on the other hand, has invested in infrastructure and opened up the country bit by bit towards a market economy. The results could not be any clearer: whereas 30 years ago, China and India were in the same ballpark with respect to GDP per capita, China’s GDP per capita is now three times the size of its Indian equivalent.

It was this very fact that Nanedra Modri made the core of his parliamentary election campaign in 2014. He promised changes by implementing overdue reforms and declared himself in favour of efficient, growth-oriented governance with the goals of the standardisation of the economic framework across India and job creation. In doing so, he hit the zeitgeist of the population who were hoping for reforms, and as a result his party achieved an absolute majority at the election – a first for any party in 30 years.

In his first term (2014 to 2019), Prime Minister Modi created a better environment for a competitive economic framework under the slogan “Make in India”. In order to make trade easier across the States, he simplified and standardised the national value-added tax system. Many investment barriers were lifted, and the legal requirements for incorporation were minimised. Lending, especially by foreign financial institutions, has been made easier as well. The introduction of expedited insolvency procedures came as significant support to the stricken Indian banking system; previously, calling on and selling bad debt had been a very tedious process. In addition, distressed banks received capital injections from the government.

Tackling the black economy

The government tackled the black economy, which the World Bank estimates to account for about 20% of GDP, with a rigorous demonetisation policy. Certain bank notes (86% of the circulating money supply, i.e. 12% of the Indian GDP) were declared void, and the conversion was strongly limited. Other fundamental data have improved significantly as well: the Indian central bank has managed to stabilise inflation, and the public budget deficit has fallen below 4% of GDP.

The results of the reforms are clear: In the World Bank’s “Doing Business Index”, which measures the regulatory environment of countries for businesses, India has jumped from 134th to 77th place within five years.

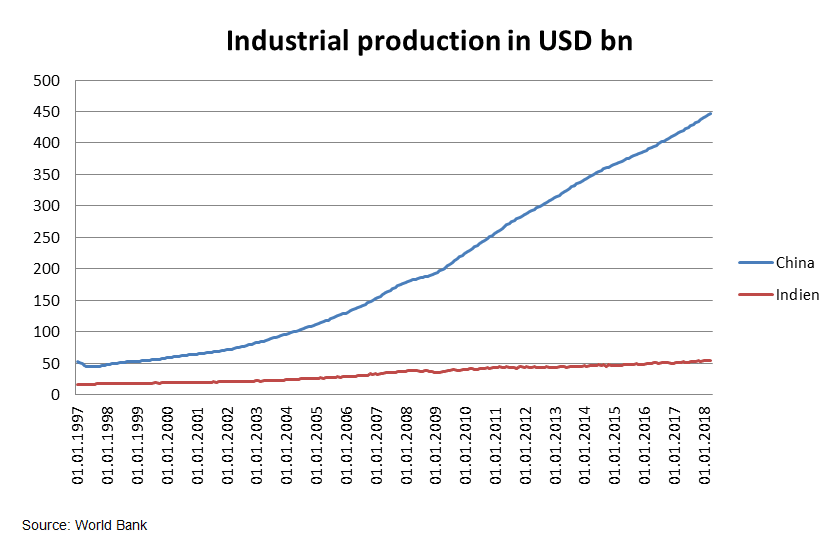

Unemployment, however, remains a big economic challenge. Despite the high economic growth rate, it has increased in recent years. We can see a chance of making better use of the existing potential in the manufacturing sector. In contrast to the service sector, the industrial sector is not growing at high rates. Here, too, the divergence between India and China over time is striking. The overregulation in the private sector in this context is one of the main reasons for the subdued growth in the industrial sector. Bigger companies in particular have to contend with a long list of regulations, which puts a brake on the sustainable growth of industrial production.

The unemployment rate has been considered one of the biggest weaknesses in the first term of Prime Minister Modi. Despite all the reforms, both intended and implemented, the unemployment rate defied the efforts and increased. As a consequence of this development, observers in the run-up to the parliamentary election in spring 2019 expected Prime Minister Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BPJ) to experience significant losses. The results were surprising: Prime Minister Modi not only retained the majority in parliament, he even increased the number of seats.

We expect Prime Minister Modi to focus his second term on improving industrial production. This includes the modernisation of the (in some cases prohibitive) labour market laws and the so-called land reform, which is supposed to install a new set of regulations about the acquisition of industrial plants. A further focus of the reforms of Modi’s second term will be the gradual privatisation of state-owned companies. This overdue step would facilitate the faster modernisation of central infrastructure projects (e.g. railways) in the country with the help of private investors.

In addition, the limitations on foreign investors with regard to the maximum investment in companies of selected sectors are to be reduced as well.

The writings on the wall

There are many signs to suggest that both the government and society are up for deep-running reforms. The political framework seems favourable not the least due to the parliamentary majorities; in this environment, even socially contested reforms could be passed. In the absence of any negative developments of external factors such as the oil price or the exchange rate to the US dollar, India would have a realistic chance to shake its status of permanent future talent and to globally establish itself as strong economy.

Since the liberalisation of the Indian capital market, more and more companies have made use of the opportunity to place international bond issues. In doing so, they do not only issue “classic” corporate bonds, but also convertible bonds in euro and US dollar. Although government bonds continue to dominate the Indian bond market, the share of corporate bonds has been on the rise. India currently accounts for 4.5% in the hard currency corporate bond index by J.P.Morgan, with more than 65% of the bonds included commanding an investment grade rating. Generally speaking, the liquidity of the bonds is very good and allows for active investment management. In addition, India currently offers a higher risk premium relative to comparable companies in China and other Asian countries. For the coming years, we therefore do not only envisage a growing (issue) market, but also an ongoing stream of interesting investment opportunities.

Want to take part in an exciting market?

The ERSTE BOND EMERGING MARKETS CORPORATE IG invests in emerging market corporate bonds with an investment grade rating. The selected securities benefit from high commodity prices and dynamic economic growth. Find out more or get it here!

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.