Table of contents

- Supranational versus intergovernmental entities

- Evolution of development finance institutions

- Projects financed by development banks

- Benefits of investing in bonds issued by development banks

- Conclusion

Supranational versus intergovernmental entities

Supranationals are defined as legal entities which are generally formed by multiple sovereigns and are thus subject to international rather than national law. They are founded to achieve a goal which all the member states have in common. A prominent example for a supranational organisation is the European Union which enhances the cooperation and integration of European countries within its borders and globally coordinates its united stance against other international entities.

A supranational, however, is not to be confused with an intergovernmental entity. The difference between the two lies in their diverse degrees of inherent autonomous decision-making power. Whereas an intergovernmental entity like the G20, a forum of the world’s major economies, has governments as its actors, a supranational entity is delegated with rulemaking and enforcement abilities by its member states.

Evolution of development finance institutions

The most prevalent form of financial supranationals are the so-called development banks (DB), the shareholders of which are the founding sovereigns or other legal entities. Also known as development finance institutions, they are established to promote the economic and social development both within and beyond the scope of the founding states.

As such, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) was chartered in 1944 to financially assist in the reconstruction of war-ravaged Europe after the Second World War, globally marking the establishment of the first ever multilateral DB. The latter designates the largest of the three major groups into which the DBs can be subdivided and is characterised by mostly having developed states as donors and developing states as borrowers.

Later, towards the end of the1950s, developing countries outside the original scope of the IBRD also emerged as potential borrowers with funding needs. Furthermore, the World Bank Group, which the IBRD is a part of, was criticised by these countries for its domination by the Western allies and for its uniform policy prescription. Consequently, to better address their own needs, regional DBs, forming the second major group, were established by developing countries themselves.

An example is the Inter-American Development Bank, which was founded with a focus on Organization of American States members aiming to reduce the level of prescriptive policies in exchange for funds and uphold own national priorities. Another property of regional DBs is that they limit non-regional states’ shareholding together with voting rights to grant regional states a stronger position. Moreover, they primarily concentrate on project and sector investments.

With more specific project and investment needs arising for certain countries, the latter even went further to found subregional DBs which typically consist of only debtors and the funds are mainly raised in international capital markets. They have both a limited scope and capitalisation, sometimes relying on funding assistance by multilateral and regional DBs.

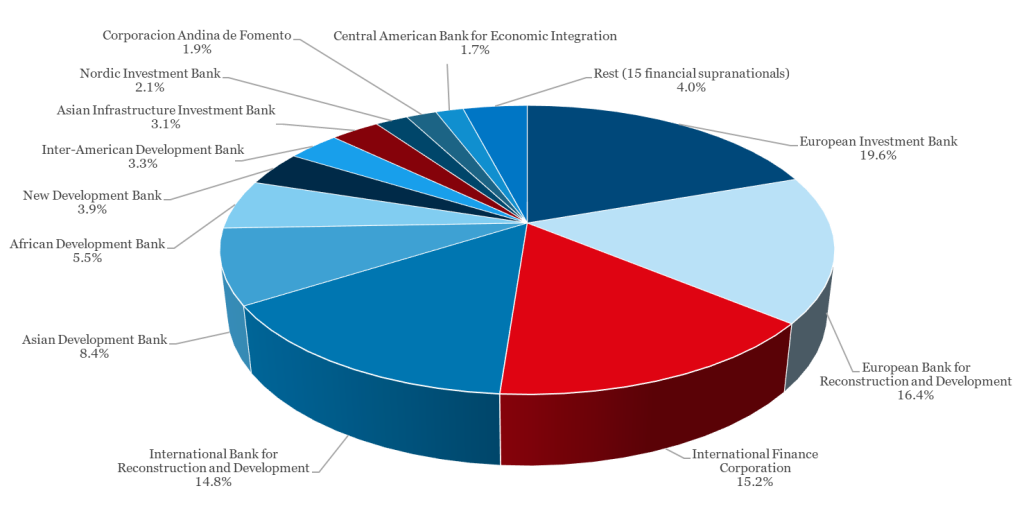

Their motivation is mostly driven by some unique common ground which all the members share. This can involve, among other factors, the focus on the issues of small island states (Caribbean Development Bank), a common cultural heritage (Nordic Investment Bank), a shared religious belief (Islamic Development Bank), the geographical situation (Black Sea Trade and Development Bank) or proximity (Eurasian Development Bank) and the spoken languages (West African Development Bank). Figure 1 shows that the four largest DBs in the market for supranationals bonds issued in emerging market (EM) currencies account for two thirds of all emissions.

Projects financed by development banks

The relevance of DBs has been steadily increasing since the IBRD was founded in 1944, when it had an initial capital base of USD 10 billion, which was equivalent to USD 133 billion as of 2013. The sum of the capitalisation of the most relevant DBs accounted to USD 1.1 trillion in the same year and thus was more than eight times larger than at the IBRD’s initiation. This positive trend is expected to further continue in the future as the demand for development projects, especially in the context of battling the climate change, is rising. Exemplary, the projects financed by DBs cover the following aspects:

- Sustainable energy

- Construct renewable energy power plants (solar, geothermal, wind, hydro, etc.)

- Increase natural gas emergency supply capacities to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and thus carbon dioxide emissions

- Build excess renewable energy storage facilities to reduce the power load on transmission networks

- Ensure nuclear safety by decommissioning old nuclear facilities and equipment

- Water resources management

- Provide drinking water access to rural areas

- Improve the water quality and security to prevent diseases and floods, respectively

- Reduce the amount of water wasting to achieve a sustainable agriculture

- Recycle water in wastewater treatment plants

- Social infrastructure

- Construct all-weather houses with access to civic amenities in urban poor areas

- Extend affordable homeownership

- Improve the educational system by building schools and nursery places

- Enhance legal protection of rights by developing judicial infrastructure and modern information and communication technologies

- Ease the access to public health care systems and healthy food

- Transportation and urban development

- Enhance transportation’s connectivity, accessibility, capacity and safety

- Build efficient and environmentally friendly public transit systems (airports, metros, railways, roads, etc.) minimising traffic congestion

- Upgrade cellular networks, internet and cloud services infrastructure

- Restore cultural heritage sites to create tourist focal points

- Economic assistance

- Modernise the agribusiness sector to be more sustainable, responsible and innovative

- Support small and medium-sized enterprises with both debt and equity financing

- Promote legal reforms to foster an investor-friendly, transparent and predictable legal environment

- Facilitate resilient and integrated financial systems through regulatory and legislative initiatives

Benefits of investing in bonds issued by development banks

All the projects mentioned above serve a common greater purpose. The idea is to boost the productivity, efficiency, safety and living standards in the countries whilst decreasing the environmental pollution and factors driving the climate change which then translates into a stronger and more sustainable socioeconomic growth. Thus, investors’ commitment to bonds issued by DBs allows the latter to finance these projects at a lower cost level which ultimately benefits the local people.

In contrast, the proceeds from sovereign bonds flow directly to the governments which then could use these funds for other purposes which might be incompatible with a bond investor’s principles and ideologies. Consequently, DB bonds are better investment vehicles for people who not only want to realise a return but also generate a positive social impact.

“Especially in a time where long-term investment grade bonds from conventional issuers like the USA or Germany yield very low or even negative returns, respectively, development bank bonds in emerging market currencies constitute a very attractive asset class.”

Tolgahan Memişoğlu, Fund Manager Fixed Income Securities

© Bild: Erste AM

DB bonds are issued both in hard currencies like the US-dollar or Euro and in EM currencies. The advantage of DB bonds in EM currencies is that they combine two favourable factors: the high credit rating of DBs and the upside potential of EM currencies. Put differently, purchasing these bonds allows investors to earn the relatively high yields which the EM currencies offer whilst avoiding the low credit ratings of EM sovereign issuers. Therefore, especially in a time where long-term investment grade bonds from conventional emitters like the USA or Germany yield very low or even negative returns, respectively, DB bonds in EM currencies constitute a very attractive asset class.

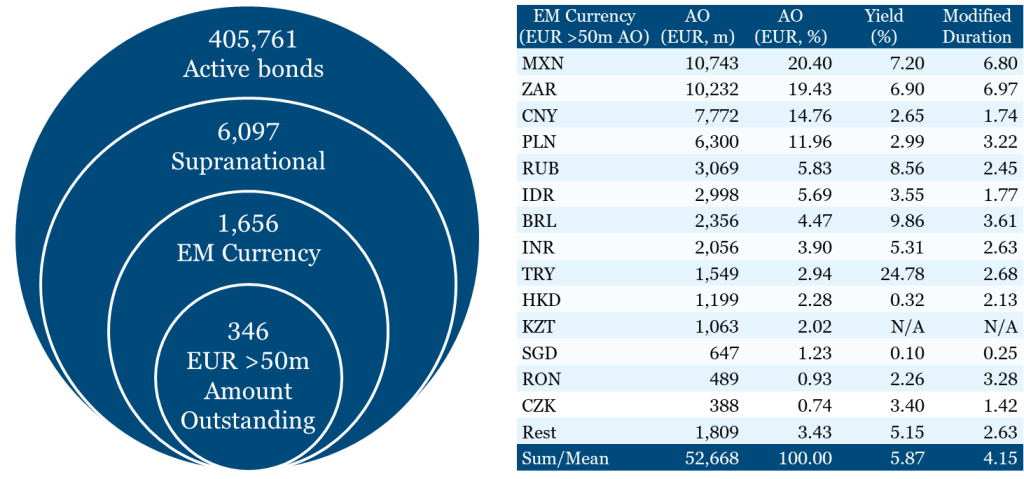

Figure 3 depicts the bond universe and its subgroups as of December 2021. At this stage, there are more than 400,000 active bonds, roughly 6,000 of which are supranational bonds. Out of these, 1,656 are denominated in EM currencies. Assuming that an amount outstanding (AO) of at least EUR 50 million acts as a liquidity threshold, then 346 supranational bonds in EM currencies remain providing a broad investment pool.

Table 1 presents the currencies and the total amounts outstanding of these 346 bonds. Their weighted average yield amounts to 5.87% per annum with an approximated capital commitment of roughly 4 years. Currently, the Mexican Peso (MXN), South African Rand (ZAR), Chinese Yuan (CNY) and Polish Zloty (PLN) account for two thirds of all liquid supranational bonds issued in EM currencies. It is expected that the market depth in this field will continue to rise as more and more investors and market makers enter this segment.

The strategic edge of DBs over EM sovereigns is that a DB’s donor states stand behind the DB as a joined guarantor group which substantially reduces its default risk due to diversification effects, especially if the DB’s members are developed market countries. Out of the 346 bonds regarded above, those which are credit rated have in more than 90% of the cases the highest rating possible, namely AAA.

This is also reflected in the course of the European Union’s Capital Requirements Directives which assign a risk weight of 0% to exposures to the most relevant multilateral DBs.[1] On the contrary, single sovereigns, especially those classified as EM, exhibit a greater credit risk as they act on their own and not seldom suffer from their own or global financial, economic and political issues.

Another benefit of having DBs as debtors is their long-standing experience in issuing bonds the proceeds of which are intended for environmental projects. DBs belong to the early movers in the sphere of green bonds and have been the only entities to issue those for some years, whereas nowadays many corporates and sovereigns use green bonds. Whilst companies are profit-maximisers and as such occasionally exploit green bonds to lure financiers via greenwashing, the risk that DBs could do so is very low as they are of public utility.

Furthermore, due to supranationals’ nature of being governed by international law, DB bonds are classified as offshore issuances making them exempt from local withholding or capital gains taxes. This is beneficial for the investor as the return on investment is not diminished, translating into a higher total return.

Conclusion

Various forms of DBs with different focuses finance social and economic projects which enhance both locals’ quality of life and the protection of the environment, thereby generating long-term economic growth. Investors can help to fund these projects by investing in DB bonds issued in EM currencies whilst realising a very attractive yield in an otherwise low interest environment with the security of high credit ratings. As the trend towards sustainable financial assets accelerates, early adopters can profit notably from DB bonds in EM currencies.

[1] Part III, Title II, Chapter 2, Section 2, Article 117.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013R0575

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.