I am writing these lines while hundreds of firemen have been fighting a fire in the North-East Spanish province of Tarragona for more than three days. The fire has already ravaged 6,500 hectares of land. Impressive, but what does that have to do with meat?

The fire was set off by the chickens of a local chicken farm. The chicken manure had started to ferment under the current heatwave and caught fire.

Meat as driver of climate change

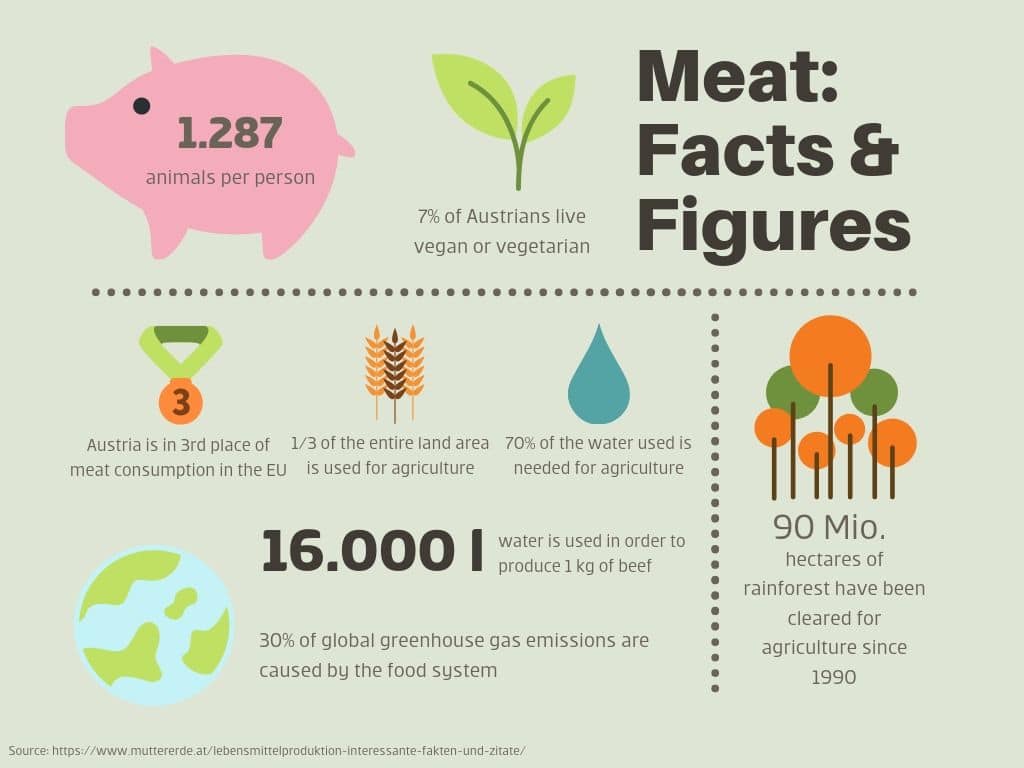

The chain reaction between meat production and climate change, which in this case concocted a dangerous mix, is one of the most significant ESG risks in agriculture. This is not only what our research partners claim: according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) some 15% of the greenhouse gases caused by man are due to cattle-breeding. The ratio of meat to dairy in terms of emissions caused by cattle-breeding is 3:1 per gram of produced protein.

Is climate-friendly meat production possible?

One of the heaviest factors in this equation is animal feed – an aspect my colleague Stefanie Schock has already addressed in another article of this ESG Letter. The choice of animal feed also affects massive discrepancies in the emissions of animals via the challenges of cultivation such as deforestation and fertilising. An intensively bred cow that is fed corn and soy produces significantly more CO2 than an animal grazing on an alpine pasture in Tyrol.

The latter also comes with the upside that pieces of land can be used for the production of protein that would otherwise not be accessible to food production. Also, the continuous growth of grass compensates for an additional 10% of emissions from global cattle-breeding according to estimates by the FAO.

Global cattle-breeding

Unfortunately, this comparably climate-friendly way of cattle-breeding does not scale up globally. Even in the enormous Australian outback, the local, extensive form of cattle-breeding is limited by the availability of water. Depending on the region, up to 16,000 litres of water are required to produce 1kg of beef. As a result, more and more herds in Australia simply die of thirst.

In the USA, the biggest producers JBS, Cargill und Tyson Foods largely depend on breeding facilities in drought areas. The climate change exacerbates the lack of water. A vicious circle.

Even though the FAO points out that emissions could be cut by up to 30% if best practice were to be followed, our research partners explain that the rising demand would pretty much cancel out this gain. The alternatives still are to consume less or use meat substitutes.

The future of meat consumption

This is also relevant since our partners regard the increase in meat demand (especially red meat) as health hazard. This is in direct violation of the third sustainable development goal of the United Nations.The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies processed meat products on the basis of the certainty of their carcinogenicity in the same category as tobacco smoke and asbestos.

Sadly, meat substitute products such as the pea-based burgers by the current stock exchange darling Beyond Meat are not beyond criticism either. While they do reduce the environmental footprint relative to traditional meat products and avoid the questionable breeding conditions of intensive cattle-breeding, their high salt content means they are no panacea either, as the analysts of our research partners explain.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.