March 2019 is already a month that will be remembered. Politicians and central bankers alike seem to be running out of options, with no quick, if any solution in sight.

Brexit is getting more confusing by the day, with a prime minister coming across so clueless as to be compared by European peers to the black knight of Monty Python who without legs and arms still refused to give up fighting. All this is happening in London, where not only the mother of parliaments is based, but also the probably biggest and most important financial center in the world.

Big question marks are hovering over both now: neither the decision makers nor anybody really seems to have a clue what comes next. I visited a banking conference for investors in London at the beginning of March, where the question was asked if there was enough risk premium priced into UK-bank bonds and how these levels would react to four different outcomes. All four possible answers did get a polling result close to 25%. This indicates the wide perimeter of the possible solutions for a way out of the low yield environment we are in.

European banks are lagging behind

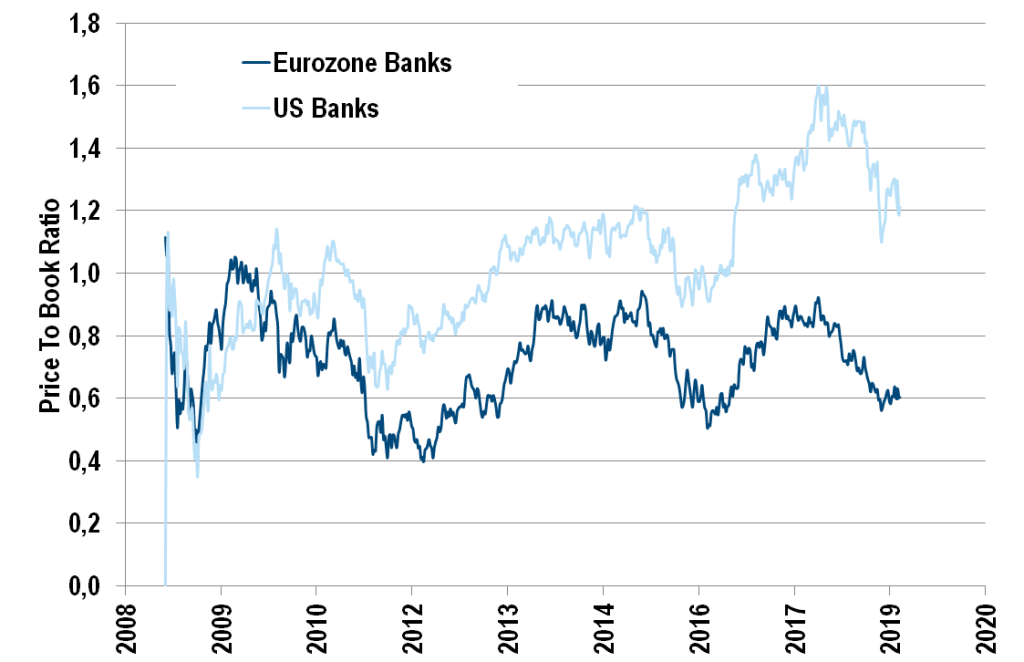

A fast-growing competitor to London as a financial center, especially in the context of the EU, is Frankfurt. Based in Frankfurt is the ECB, which also came under the spotlight in March. The ECB surprised markets with the announcement of a fresh round of targeted lending to banks. It was expected to come, but not as early as now. Although this was necessary to alleviate the worries over European banks, the FTSE-Eurofirst 300 Bank index fell by more than 3%, the worst day of the year so far. European bank equity is trading at less than two thirds of its book value, whereas the US banks are trading at 125% of their book value on average. What has gone wrong with the financial sector in Europe during the last ten years?

Negative interest rates are one of the reasons why especially the stronger European banks get punished, with banks having to pay billions a year to the ECB at the deposit facility rate on their excess reserves, whereas US banks receive a multiple amount of that on their excess reserves. This state of affairs will now last longer than previously expected. The, historically speaking, still high rates of non-performing loans especially in peripheral countries do not help the profitability of the banking sector, either. Probably most detrimental is the implementation of a very strict new set of regulations, which is meant to make the banking sector less risky, and countries will not be forced anymore in the future to bail out their banks when they are in trouble either. Mr. Draghi surely did not expect the banking sector to still need this much help at the end of his tenure with the ECB.

Price to Book Ratio

Price to book ratio, Quelle: EAM

What the financial crisis has shown us

A big lesson from the financial crisis is that big banks were taking far too much risk, enabled by the inevitability that governments would have to rescue them from any serious difficulties, because failure would have disastrous consequences for the economy in general. Lehman was the experiment gone-wrong, which exemplified the creation of moral-hazard for institutions that were considered too big to fail.

So, how come at a time when most developed economies are still dealing with the fall-out of the financial crisis and the ECB can still see no other options than to give away money for free to European banks in the hope that at some point in the future they might be able to stand on their own feet again, German politicians can think of no other solution for Deutsche Bank than to let it merge with another struggling German bank, thus creating a bank that qualifies even more clearly for the too-big-to-fail badge?

The proponents of the merger mainly argue that German and European Banks are too fragmented to be competitive, compared to other global banks, especially the ones from the USA. This is not hard to argue: the bigger the better, better to be a price-maker than a price-taker. But isn’t that exactly what free market apologists argue exactly the other way around? All other things equal, this cost will ultimately be paid by the German banking clients, with the new local top dog achieving bigger margins from its customer base.

As always with a merger, especially one on this scale, synergy is meant to reassure any critic. This will come with a huge social cost though. According to estimates, the transaction could cost up to 20,000 jobs, which is challenging to explain for even the most cynical politician.

Why don’t banks look for partners abroad?

Two entities lacking profitability on their own will hardly become more profitable once combined, as far as ROCE and ROE are concerned. On the contrary, the estimated capital needed to make the new bank viable will be around EUR 10bn on the face of it. So, even more capital over which to spread out already meagre profits.

So, even if the merger between Deutsche and Commerzbank does go through in whatever form, we should not expect any improvement in ROE. And I am not even addressing the intangible difficulties that any merger of that scale creates.

Deutsche Bank in particular still has a lot of homework to do. Of the two, Commerzbank is now in a relatively clean position, and it is hard to imagine that it wishes to merge with DB at this stage, given the difficulty in assessing the potential of write-downs in DB’s investment bank division. Which raises the question: if the need is felt that these banks should find a partner, why not look at the possibility of a cross-border merger? If you consider the European Union as a whole, there are definitely better-suited candidates for each of the two banks, which would also be a very strong signal towards further integration of the European Financial System. However, in order to make progress towards the completion of the banking union, the regulated protagonists would also need support from the regulators. As long as liquidity requirements have to be met at the subsidiary level in each country rather than at the parent domicile level, the economies of scale of cross-country European banking mergers are impaired. The protection of national deposit insurance schemes prevents banks from managing liquidity centrally at the parent level.

All this illustrates the difficult and painful decisions that have to be taken for and by the European banking sector as a whole.

Meanwhile an equity problem

Regarding the (way) too-big-to-fail institute to be created from this merger, one should consider the following: when this argument first came up, the environment was entirely different. Capital ratios were much lower than now, so-called total loss absorbing capacity has improved markedly over the past couple of years; hence, the above-mentioned stricter regulation is not just bad, but rather, there is very good reason for it. The risks are clearly lower than they were ten years ago. This comes at a cost though, making it harder for a bank to create profit per shareholder as the bank will have less to spread across more capital, which also explains why European bank equity has been so clearly lagging behind the rest of the European equity index since 2009.

For European banks, it is an equity problem and not a debt problem anymore. As also illustrated by the reaction of the credit default swaps after the ECB announcement, while bank equities were tanking, the credit default swaps on the same names hardly moved, despite the strong tightening since the beginning of the year.

The only sustainable way out might be to leave this negative yield environment behind us, but as long as the inflation and growth forecasts stay low, this will not happen anytime soon. Besides, as long as the non-performing loans are as high as they are at the moment and total loss absorbing capacity and net stable funding ratios have not been met yet, too many banks will continue to rely on the ECB for their funding.

Until then, low profits are here to stay, which is arguably the cost of a more stable and far less risky banking system. In its ultimate, intended form, it would create a more stable and more prosperous EU-economy, vital for the success of the European Union as a whole. That might also be the rationale of the proponents of the merger between Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, whereas I would suggest that considering much more viable cross-border mergers would be preferable.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.