The majority of economic indicators continues to suggest weakening global real economic growth. The global purchasing managers’ index for the manufacturing industry in particular continued the falling trend in February, thus suggesting prolonged weakness in the manufacturing sector. While there are some weak signs of the downswing coming to an end in the coming months, uncertainty remains elevated. The central banks have reacted to this and have suspended the planned increase of key-lending rates or have indeed taken steps to loosen the monetary policy again. At the same time, the market prices already reflect the stabilisation of economic growth. How can this dichotomy between the market and the economic environment be resolved?

“Normal“ slowdown

The weakening in economic growth can partially be attributed to a “normalisation” in the sense that growth rates have declined from above-average to average. That being said, the general tightening of central bank liquidity and the increase in uncertainty have also contributed to the situation.

Lower central bank liquidity

Motivated by the strong economic growth in recent years, the central banks in the developed economies have launched a policy of gradual “normalisation”. This means the increase of the very low key-lending rates and the discontinuation of the bond purchase programme and divestment of the bonds thus acquired. This has led to a decline in the money supply (M0), which had been expanded drastically by the central banks.

Shrinking of the shadow banking sector in China

At the same time, some emerging economies experiencing disequilibria have come under pressure to raise their key-lending rates in the wake of the rate hikes in the USA. In China, the economic policies have focused, among other things, on shrinking the shadow banking sector. This path was chosen due to the high ratio of debt to nominal GDP and China’s intention of preventing the ratio from rising any further, which in turn caused credit growth to weaken significantly.

Increase in uncertainty

The uncertainties concerning the future relationships between the big economic blocs have increased as well. The trade conflict between the USA and China is a case in point. The chaotic Brexit process and the doubts over the integrity of the Eurozone (Italy) have also contributed to the situation.

Sentiment in the business sector deteriorating

The decline in the business sentiment is a direct effect of this unfavourable combination of factors, and it weighs on growth and capex in the corporate sector. By contrast, employment growth has remained relatively strong (i.e. low unemployment rate). As long as the labour market remains solid (i.e. good employment and wage growth), private income and private consumption are being supported. The catch is that the labour market is a lagging indicator. While the surprisingly low increase in employment in the USA in February (+20,000) in comparison with the 5Y average of +215,000 is not statistically significant, it does nothing to mitigate the uncertainty prevalent in the market.

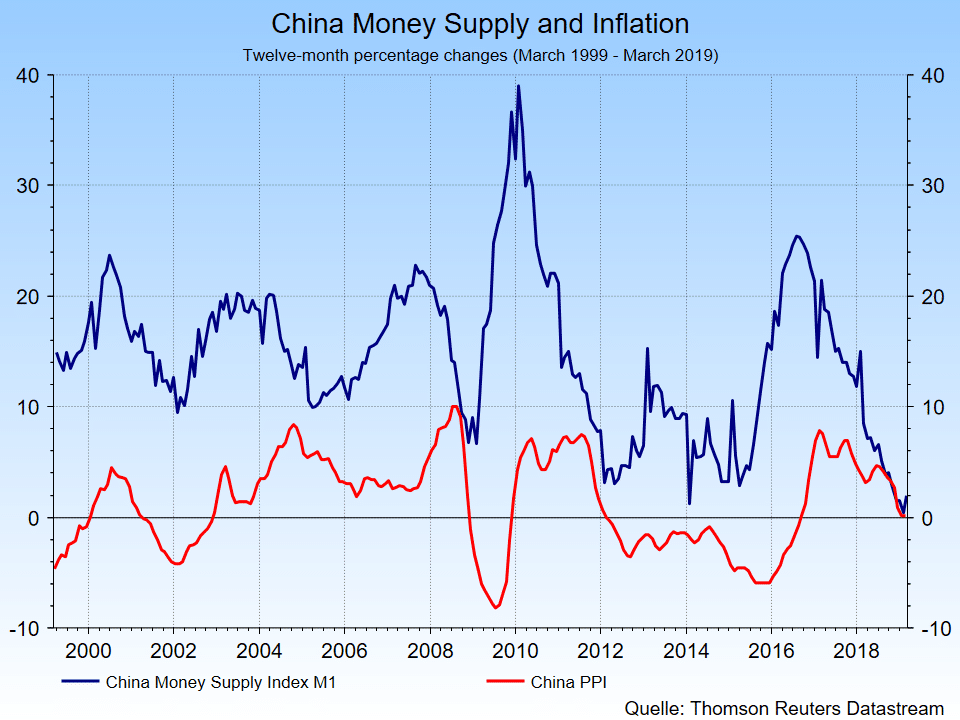

Chart: Money supply and producer prices and their growth rates in China are important global economic indicators

Recovery on the financial market

The financial market reacted with drastic losses of risky asset classes (equities) in Q4 2018 to the deteriorating environment. The benchmark for positive surprises was therefore low – and as a result, in they came:

- Some important central banks loosened their monetary policy. It should be noted that the rate hikes by the US Fed previously priced into the market have completely disappeared. However, continued wage growth would put the Fed between a rock and a hard place: should it focus on employment or inflation? The increase in average hourly wages in February to a level that we had last seen ten years before did not help.

- In the Eurozone, the ECB pursues a strategy that implies the relaunch of a monetary instrument (TLTRO – targeted longer-term refinancing operations for banks in large volumes) in order to boost the resilience of the banking sector and thus the entire Eurozone economy. Also, the ECB has pushed back the earliest date of its initial rate increase to the beginning of 2020. However, the room for manoeuvre is limited for the monetary policy. The similarities to a so-called liquidity trap (Japan scenario) are clear.

- In China, credit growth has recently increased. At the same time, important indicators such as money supply (M1) growth and producer price inflation are falling.

- The signals sent out in connection with the negotiations between the USA and China give reason for cautious optimism. That being said, in addition to the still elevated likelihood of the negotiations failing, there is also the risk of tariff hikes on goods exported from the EU to the USA.

- Brexit: in the short run, an extension is gradually turning into the most likely scenario. The UK will probably still be a member of the EU in April for a few more months. But an “accident” (i.e. a hard Brexit without any agreements) may still happen.

- The signals of stabilising growth are there, but only just. They include indicators such as the global purchasing managers’ index for the service sector, which increased in February.

Conclusion:

The majority of leading economic indicators are still falling, and the retreat of globalisation may have only got a short reprieve. At least the central banks have stopped their policies aimed at tightening liquidity, or have even reversed it. For the recovery of the risky asset classes that we have seen in the year to date to continue, growth would have to stabilise. Since the signs of that happening remain too weak, prices have been on the decline since the beginning of March again. As long as no geopolitical deterioration takes hold (negotiations between the USA and China, between the USA, the EU, and Japan, and between the UK and the EU), there is a chance that the stimulus measures (more liquidity) may facilitate the stabilisation of economic growth with a time lag of a few months.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.