New British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is preparing Britain for an unregulated withdrawal from the European Union. Theresa May’s successor has formed his government team from Brexit hardliners for the most part, and in case there are no further negotiations and concessions on the part of the EU, the UK will leave the Union on 31 October of this year without its own contractual regulation of future relations, London says.

A hard Brexit has long been described as the most economically unfavourable outcome for the first EU withdrawal in history, but now this worst-case scenario could indeed become a reality.

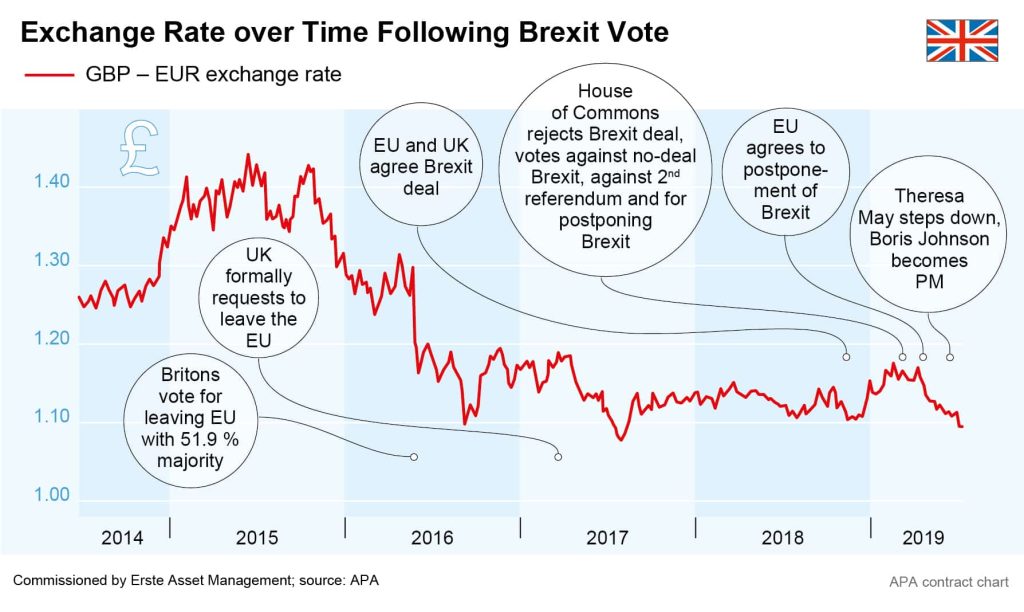

The UK is already feeling the massive consequences of the economic uncertainty caused by the Brexit –particularly evident in the exchange rate of the British Pound, for one.

Historical lows

The economic risks posed by the Brexit are strongly impacting the value of the British currency. Immediately after the Brexit vote in June 2016, the Pound had fallen to its lowest level in over 30 years. After a narrow majority of 51.9 per cent for the withdrawal, it dipped below the USD 1.35 mark.

More than three years and three heads of government later, the Pound’s exchange rate in the lay at USD 1.21 last week.

Since the vote, the Pound has depreciated by slightly more than 13 per cent against the euro, falling by 2.8 per cent in the past 12 months alone. The exchange rate has a strong impact on equity investments and investment products traded in the financial metropolis of London.

On the stock market, however, the currency’s significant losses are countered by a fundamentally positive trend. The London Stock Exchange’s leading index FTSE-100, for example, has risen by more than a fifth since June 2016. While a lower Pound rate makes British products outside the Kingdom more attractive, it will be more expensive for Britons to buy from the eurozone, for example.

However, the decisive factor for the further development of economic relations with the UK will not be exchange rate effects but trade barriers. A hard Brexit would raise expectations of increased legal uncertainties, customs duties and red tape.

Countermeasures in fiscal and monetary policy

Even the new government in London seems to be convinced of this: last week an additional GBP 2.1bn were estimated for hard Brexit preparations, bringing the total the Ministry of Finance has budgeted for the current financial year in order to be prepared for a no-deal Brexit up to GBP 4.2bn.

434 million Pounds are to be used to ensure medical care through additional freight capacity, warehouses and stocks. One of the big issues will likely be the border between EU member Ireland and the British province of Northern Ireland, where border controls threaten to slow down and make the transport of goods more expensive.

Meanwhile, the Bank of England does not want to automatically change its interest rate policy in reaction to a hard Brexit, said BoE Governor Mark Carney at a hearing in Parliament in late June.

The British monetary authorities recently unanimously left the key interest rate unchanged at 0.75 per cent, while stressing that a “gradual and limited” tightening of the monetary policy would be necessary in order to achieve their inflation target in the coming years.

However, an interest rate hike would be subject to the proviso that the Brexit succeeds smoothly – an assumption that is currently becoming, if anything, less probable. In addition to supply and demand, the BoE’s Brexit reaction should take the Pound exchange rate into account, Carney said.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.