Italy, the third-largest economy in the European Union, has voted. This means that the term of office of the “all-party government” of Prime Minister Mario Draghi is coming to an end. Draghi continued in office on an interim basis despite having resigned in July. What effects this will have on the country and on cooperation in the European Union remains to be seen.

The election result

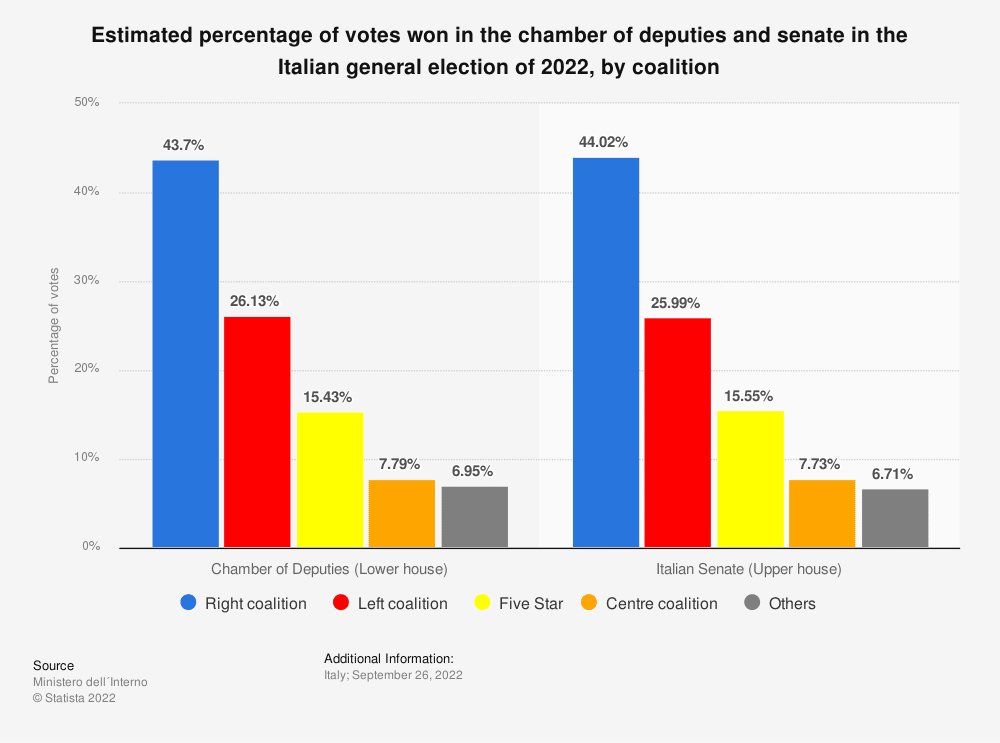

In the course of the parliamentary elections held last Sunday, the future representatives of the two political chambers (Senate, Chamber of Deputies) were newly elected (for the first time since the electoral reform of 2020, now reduced to a size of 200 and 400 seats, respectively). The big winner of the elections is the party “Fratelli d’Italia” around top candidate Giorgia Meloni. It received about 26% of the votes, making it the party with the most votes. The centre-right alliance favoured in election polls, consisting of the three parties “Fratelli d’Italia”, “Lega”, and “Forza Italia”, won an absolute majority in both chambers with about 43% of the votes. Giorgia Meloni is about to be elected as Italy’s first female prime minister. However, a two-thirds majority was not achieved. It would have made any future constitutional changes in a potential government more facilitated.

The centre-right alliance

In contrast to the other two parties in the alliance, the party of Giorgia Meloni (“Fratelli d’Italia”) was not represented in the all-party government under Mario Draghi and scored with protest voters in this election. As opposition leader, it has managed to rise politically in recent years with issues such as freedom, national pride, Italy’s right to self-determination, and criticism of the EU, as well as the representation of conservative values and stricter migration and asylum policies.

Matteo Salvini (“Lega”), as former Minister of the Interior, positioned himself primarily as an advocate of security and migration policy as well as conservative values. However, cohesion within the party has been further weakened under Salvini’s leadership. Especially in the North of Italy, the, in some cases, radical views meet with limited success. The political veteran Silvio Berlusconi (“Forza Italia”) promised above all tax relief, a flat tax in the area of income tax, and pension increases.

How the balance of power within the alliance will develop remains to be seen. While the “Lega” was still the strongest of the three parties in the alliance in the last parliamentary elections in 2018, after losing 8.5% of the vote it is now only at just under 9% and thus only slightly ahead of the third alliance partner, “Forza Italia”, which also suffered heavy losses.

Outlook: limited budgetary leeway

Important decisions are to be taken in Italy in the coming weeks and months. If the parties agree on a joint government, the following issues will be among those to be addressed and prioritised in a new government:

- Budget negotiations

- Migration and asylum policy

- Family policy

- Minority rights

- EU scepticism

Budget negotiations in Italy traditionally take place in autumn in order to facilitate the passing of a budget by the end of the year. Depending on how long it takes to form a government, the available time window is not excessively large. In addition, concrete proposals for support measures for the population and businesses, tax relief, and economic policy must first be negotiated or substantiated, and the budgetary leeway is likely to be limited due to the very high national debt compared to the EU.

Note: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance.

Potential tensions between the new government and the EU could arise over the issue of migration and refugee policy: Italy could step them up and demand concrete negotiation results or commitments from the EU. Also, Giorgia Meloni wants to renegotiate with the EU the conditions for the almost EUR 200bn in disbursements from the Next Generation EU Fund until 2026 (about two thirds thereof in the form of loans, one third in the form of grants) agreed under Mario Draghi (core areas: ecologisation (37%), digitalisation (25%) as well as education and healthcare, at least partially. In view of the potential for conflict, the election campaign began to word many statements in this regard in a deliberately diplomatic manner vis-à-vis the EU.

Note: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of an investment.

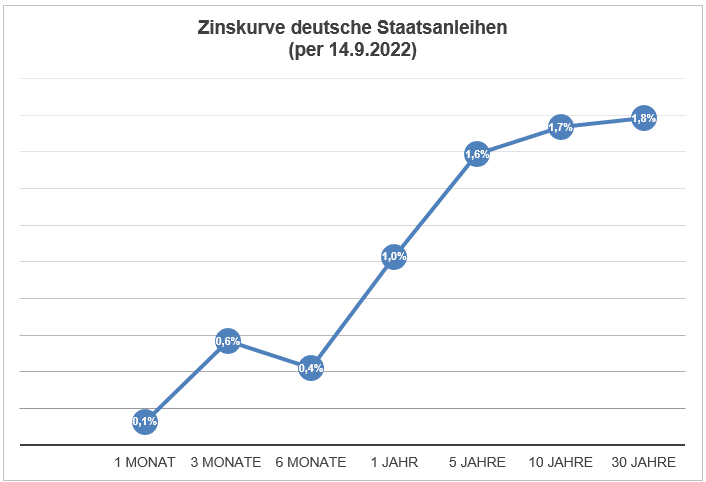

The spreads on Italian government bonds vs. German government bonds have widened over the course of the year and are currently at 2.5% for a remaining time to maturity of 10Y. Italian government bonds with a remaining time to maturity of 5Y currently yield just over 4%, including a spread of 2% (source: Bloomberg, 27 September 2022).

Conclusion

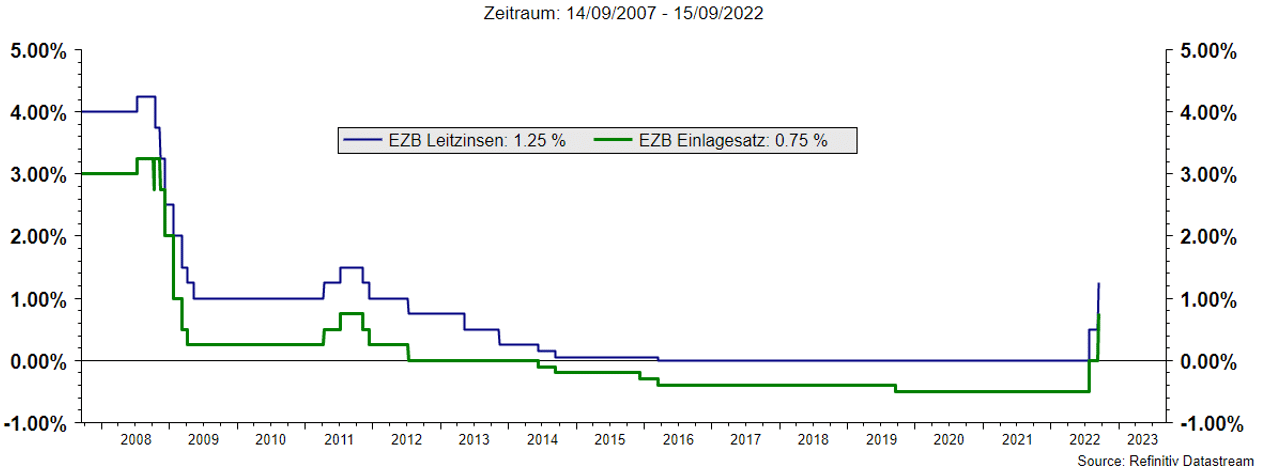

A new Italian government will be facing major challenges. Although tensions under a centre-right alliance government with the EU are likely to increase in many respects in the medium term, the short-term benefits for both sides could outweigh the disadvantages. Reinvestments from the bond purchase programmes, the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), and payments from the Next Generation EU Fund would be useful support measures for the Italian economy and could contribute significantly to limiting government debt and financing a rising interest burden to a sustainable extent in the coming years. It therefore remains to be seen what sort of action will follow Giorgia Meloni’s sometimes calamitous choice of words in the election campaign and to what extent Italy is prepared to risk conflicts with the European Union or allow them to escalate.

For a glossary of technical terms, please visit this link: Fund Glossary | Erste Asset Management

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.