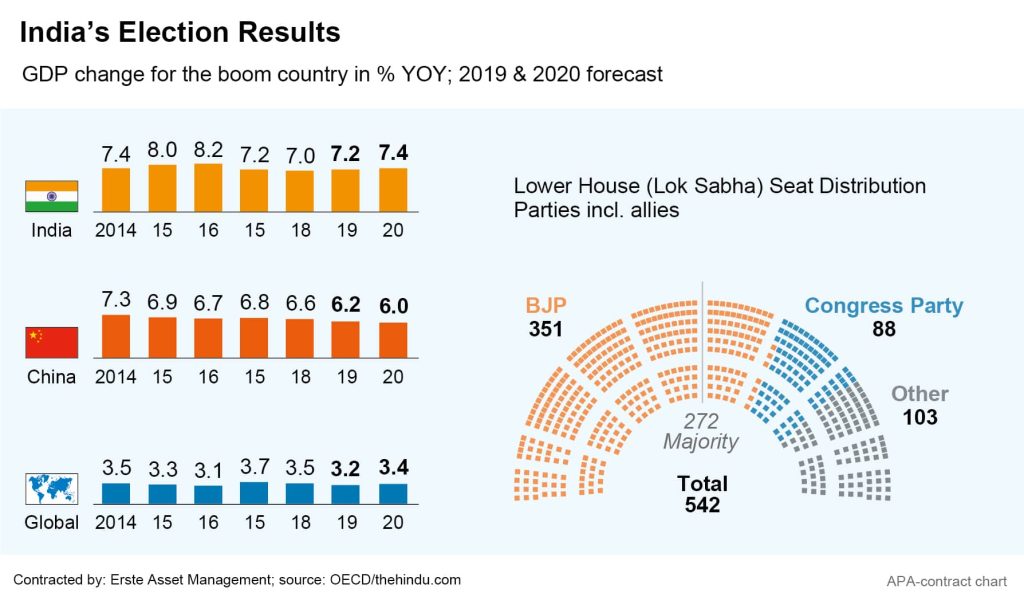

India is considered the largest democracy in the world, and that is not the only superlative in connection with the national parliamentary elections in May: With about 67% of the 900 million citizens entitled to vote, the elections saw the highest turnout ever. The winner of the ballot was the ruling party BJP, and particularly the incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The “Party of the Indian People” gained a considerable majority of 303 of the 545 seats in the lower house of parliament. Despite a fair amount of scepticism, the ruling party performed much better than in the previous parliamentary elections in 2014, when it was the first party to achieve an absolute majority (of 282 seats) in 30 years.

In the last three regional elections before this year’s national parliamentary elections, Modi suffered significant losses. Right up to the elections, surveys did not suggest that his Hindu-nationalist party, increasingly regarded as populist, would achieve a major triumph, primarily because of economic challenges. Modi had promised millions of new jobs and was unable to keep his promise. The fact that he was able to succeed is primarily attributed to security issues in connection to conflicts, among others, in the Kashmir region.

Significance of Indian economic policy beyond the country’s borders

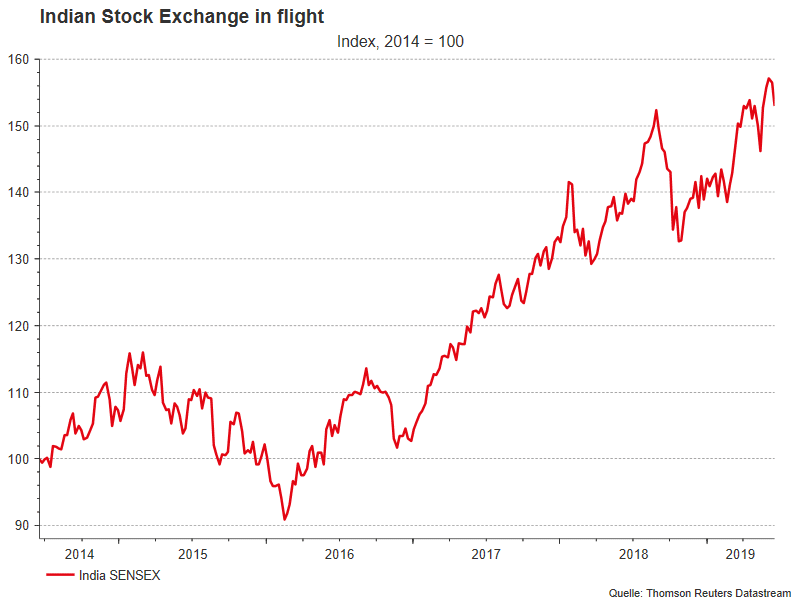

Nevertheless, Modi’s economic policy will be of particular significance during the five years of his second term, not only for India, but also for the global economy. In its most recent forecast (May), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) expects India’s economy to grow by 7.2 per cent in the current year and 7.4 per cent in 2020. This means that India’s GDP is expected to grow even more strongly than China’s (6.2 and 6.0 per cent, respectively). The OECD forecast sees India growing more than twice as fast as the global economy in the respective two years. During Narendra Modi’s term in office, the Indian economy also performed exceptionally well. The Indian stock market showed near-continuous growth, and investors appear to have been satisfied with his surprisingly decisive re-election: In the period around the publication of the election results and the swearing-in of the new-old Prime Minister, the Mumbai stock exchange’s leading index, Sensex 30, broke well through the 40,000 mark. Over the past three months, Sensex has increased by 4.5 per cent and is now a good 10.8 per cent higher year-on-year. The index managed grow by more than 50 per cent over the last five years (Source: Bloomberg, 18.6.2019).

Note: Past performance is not indicative of future development.

One important factor for the strong economic development also constitutes a challenge for India: the extremely young population that makes growth possible on the one hand and needs a functioning employment policy on the other. In addition to internal risks, there is a growing problem that many economies around the world are now increasingly facing: protectionism.

US tariffs following the elections

Only a few days after the results of the six-week elections in India were published, US President Donald Trump cancelled tariff concessions on Indian trade with the US. On 5 June, Trump declared that India’s special treatment under a trade programme for developing countries was being cancelled as India did not grant the US “fair and equitable” access to its markets.

On the day after the tariffs on Indian exports to the USA came into force, the Indian central bank lowered its key interest rate by a further 0.25 per cent to 5.75 per cent for the third consecutive time – this lowest interest rate since 2010 is bound to increase the wiggle room for the Indian economy somewhat. Nevertheless, Modi is expected to make clear economic policy decisions with regard to employment and the exacerbated supply situation soon. After the landslide victory in May, parliament can be expected to back any such decisions: last Sunday, the Indian customs authorities finally announced that they would increase customs duties on 28 products from the USA, some of them massively.

Indian stock investment

Investors wishing to participate in the development of companies from emerging economies can do so through equity funds such as the ESPA STOCK GLOBAL EMERGING MARKETS. The invested capital is distributed across different regions, companies and sectors. Listed companies from India are currently weighted at 10 per cent in this fund. Entry is also possible through an s Fund Plan, whereby the higher probability of greater price fluctuations compared to other asset classes should be taken into account.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.