Comment by Péter Varga, Senior Professional Fund Manager ERSTE BOND EM CORPORATE

For Boesky, who was always on the lookout for capital for his arbitrage adventures, a savings and loan (S&L) would have been an inexhaustible source of funds. But whatever he would have wanted to do with the capital, Milken and his staff could wait in the sidelines, well aware where the largest part of the money would be going: into junk bonds that Milken had selected as investments.”

James B. Stewart: Den of thieves

This story is based on a true incident from the 1980s. Boesky was an arbitrageur, a trader who spotted valuation differences in different markets, and Milken was the king of “junk bonds.” Both were later convicted of insider trading, among other charges.

What does this have to do with a story about Evergrande? Have a look at this Bloomberg report from 27 May 2021: “China Evergrande Group, the country´s most indebted developer, slid in the credit and stock market Thursday after a local media report, that regulators were looking into dealings with a banking unit that owns its bonds.”

The article goes on to describe how the company Evergrande increased its investment (funded by a bond issue on the capital market) in Shengjing Bank Co. in 2019 and how then the bank was buying Evergrande bonds (transaction value: USD 15.7bn). A very creative, but not exactly innocent approach. Having read that, I immediately sold my remaining, small position in Evergrande at about 97.

What, then, is Evergrande, and why are the newspapers full of the story?

As the name itself would indicate, the owner does not suffer from an inferiority complex: (for)ever grand? The Chinese tend to go for somewhat bizarre names: going through the names of construction companies, you will find daughters’ names; EASY TACTIC LTD (for the bonds of Guangzhou R&F Properties), regardless of the fact that companies may well be close to default; TRILLION CHANCE, or SINCERLEY JOURNEY.

Hui Ka Yan, chairman and majority owner of Evergrande, has an exemplary résumé as far as the values of the Communist Parties are concerned: he grew up in poverty, and after the reforms of Deng Xiaoping he started to build houses in the 1990s in the South of China. He has been a member of the Chinese Communist Party for more than 30 years. He was always at hand when it came to public displays of support for the CCP and its goals: China has ambitions in football, so Evergrande built a team and pumped millions of USD into its efforts; in 2014, the team was sold to Jack Ma from Alibaba.

In the field of electromobility, the China Evergrande New Energy Vehicle Group operates hospitals and nursing homes while also developing electric cars (and is no longer able to pay its employees). Evergrande has also shown its support for cultural goals such as the motto of common prosperity, which has been spread more and more prominently in the past three to four years.

Hui Ka Yan is a well-behaved philanthropist and makes a lot of donations, like most recently USD 115mn for the Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases. A well-behaved billionaire, then, as far as the Party is concerned – unlike Jack Ma et el, who still have to learn their lesson…

4% of the total market

Evergrande, whose revenues account for 4% of total revenues of the market, builds most of its houses in rural China, i.e. not on the east coast, where everyone wants to go, but inland, where the idea is to lure the rural population to the cities, for example to Chongqing, as there are more jobs available there. These houses and apartments are also not taken over by new residents or sold that quickly, so they appear longer in the balance sheet of the companies. However, with Evergrande, they were not classified as inventory but as investments, which meant the company was free to ratchet up the valuation of these properties and parking lots even though they did not create any cash flow (as they remained vacant/unsold).

This also inflated the company’s equity. As some Bloomberg reports have also confirmed, only a year ago the owner was bragging to make Evergrande one of the 100 most valuable companies in the world, with more than CNY 1,000bn (USD 134bn) in assets and CNY 800bn (USD 107bn) in revenues. While assets might reach such book values, are they really worth that much? Are they backed up by cash flows that support this valuation? How are the assets financed? And this is the crux of the story. The company was apparently in constant liquidity trouble due to its rapid growth. Suppliers and lenders had to be paid even before the properties could be sold. Hui Ka Yan would resort to the advances paid by the clients more and more often which were available depending on the building code. But even the suppliers were then forced to invest part of their claims in the financing products of Evergrande if they were to keep getting orders from the company.

Employees were advised to invest in products that offered to pay upwards of 25% in yield; such products were hardly ever redeemed and instead just extended. The financial subsidiary of the company also issued products that made similar promises and were re-packaged as so-called WMPs (wealth management products) and sold to the private clients of banks. This product category had grown so massively at some point that China put up limitations, which triggered a small panic on the real estate market.

This created a huge network of invested companies and individuals, “stakeholders-by-force” on the basis of loans, equity investments or project participation who had a vested interest in the fate of the company. Capital and interest payments were settled by taking on board an ever-increasing number of new creditors. A Ponzi scheme had emerged.

Speculative real estate purchases dominate the real estate market I.

Multiple property owners bet on quick profits in real estate boom

Characteristic of many home construction companies in the Middle Kingdom

These methods – albeit perhaps not quite as aggressive – are typical of many residential construction and development companies in rural areas. That is why China wanted to regulate the sector by drawing up three “red lines” – thresholds of three debt and liquidity ratios that companies had to fulfil by 2023. This reminds me of product regulation efforts for banks, where banks have always been creative in the development and use of new products such as sub-prime mortgages with varying terms, some of which had devastating effects that took the regulator some time to catch up with. Case in point are many companies that have reduced their “official debt” recently while their off-balance sheet liabilities (such as joint ventures) have increased almost exponentially. Debt cannot be magically wished away – it can only be converted or restructured.

The role of land sales in revenues of local adminsitrations

The global real estate industry

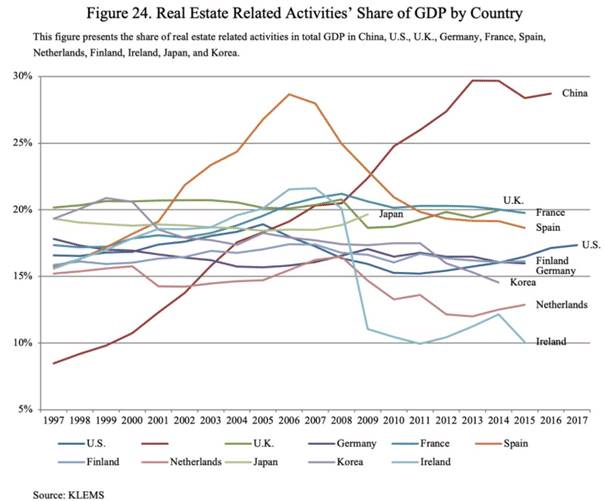

The reason why a big developer that has got into trouble is such big news is the fact that according to estimates this sector accounts for about 30% of GDP.

In simple terms, this is how the real estate business works: the local administration sells land in order to finance its spending. Developing companies buy it (highly leveraged) to build – sometimes in very rural areas – houses and apartments that are either taken over by the buyers as place to live or that are held as investment vehicle in the form of empty real estate.

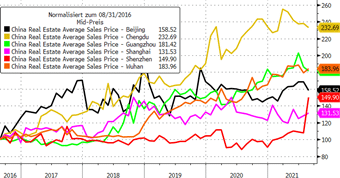

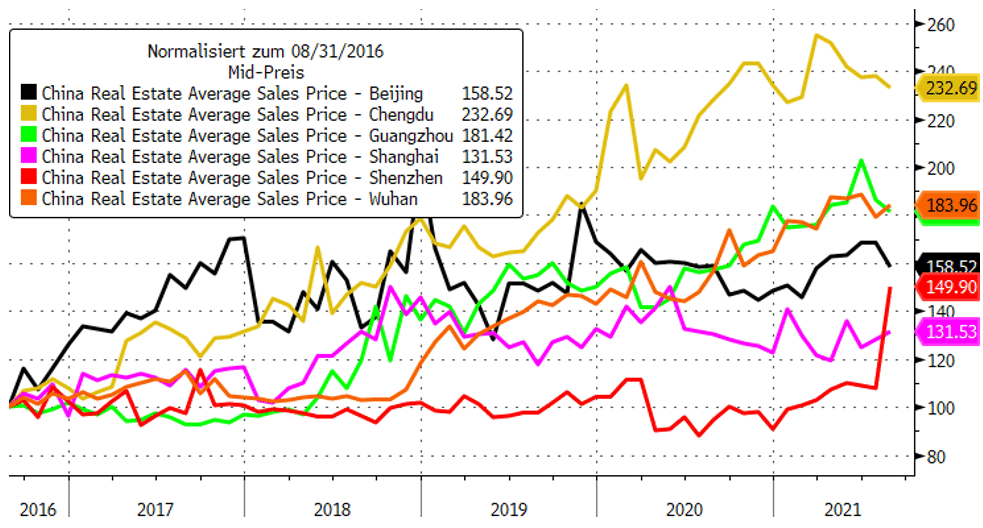

Prices rise because the hoard of buyers becomes bigger and bigger, the owner benefits from rising house prices without having to worry about rents. After property prices had increased substantially (Chinese cities are among the most expensive ones worldwide), more and more people were able to buy real estate on credit.

If the trust in this trend were broken (e.g. because of developers going bankrupt, not finishing their projects, or offering a significant discount to sort out their liquidity situation), the consequences for the economy could be dire – also on a global scale, since China accounts for about 60% of global demand for commodities.

Is there a solution to the problem?

Yes, there is. First of all, China has to make sure the projects of Evergrande are completed and has to issue a guarantee to this effect, if necessary (like it did with savings in the banking sector). The state has to intervene. The real estate market must not succumb to a crisis of trust caused by a sell-off on the real estate market. After all, this sector accounts for 30% of GDP and 60% of household savings, with a tight network of mutual claims to boot (local administration, developer, supplier, savings). A crisis of trust can set off a fatal chain reaction, and we are closer to one than ever before.

Can this strong upward trend of house prices continue?

Probably not. The growth rates are on the decline, and there have been signals from the “top” that property earmarked for leasing would be considered preferable to property owned outright in the future. Some provinces have started regulating the prices of real estate transactions; prices cannot rise by more than 5% or fall by more than 15% per year. This is how China works. I wonder what companies will be doing that pay 10-20% interest on the market and that have had their property price increases capped while commodity prices are constantly rising and labour is not as cheap as it used to be (N.B. not for nothing has China recently been selling commodities on the market in order to push prices down).

They will probably go bankrupt. The economy will be wobbly for a bit and then consolidate. China is facing a difficult tightrope walk ahead, after all, property price appreciation has kept China’s consumption alive in recent years and given jobs to millions of workers from rural China. The loans and payment obligation chains could now challenge that in the future.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.