Last weekend, for the third time in two months, a US bank found itself in turmoil. After Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) slid into crisis in March after customers withdrew billions in funds, First Republic Bank was hit. Last weekend, the bank was taken over by the major US bank JP Morgan Chase as part of an emergency rescue.

The negative effects of the key interest rate hikes

Until March, the key interest rate hikes had hardly any negative impact on the real economy. However, this changed abruptly when the first financial institutions began to falter and herd panic spread across the financial markets. Even a déjà vu of the Great Financial Crisis of was conjured up, which only fueled the panic.

One now almost gets the impression that there has been an accumulation of banking crises and bank runs since the beginning of the millennium due to mismanagement and inadequate risk handling. Public discourse is rightly asking whether financial market stability is at risk and whether lessons learned from past crises may not be enough.

SVB bankruptcy puts an end to strong start to the year

The start of the year 2023 was a brilliant one for banks and financial stocks on the international markets. In Europe, the Financial Services sector posted a YtD performance of 7% as of 08.03.2023. However, when Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) announced a day later that customers were withdrawing deposits on a large scale, the party came to an abrupt end. The bank had to sell government and mortgage bonds with massive book value losses to service the outflows.

Although the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) stepped in, declared SVB insolvent and took control, customers withdrew nearly a quarter of total deposits in a single day. Calm was restored only when a new liquidity assistance program was launched in cooperation with the Federal Reserve. In retrospect, however, this turned out to be the literal calm before the storm.

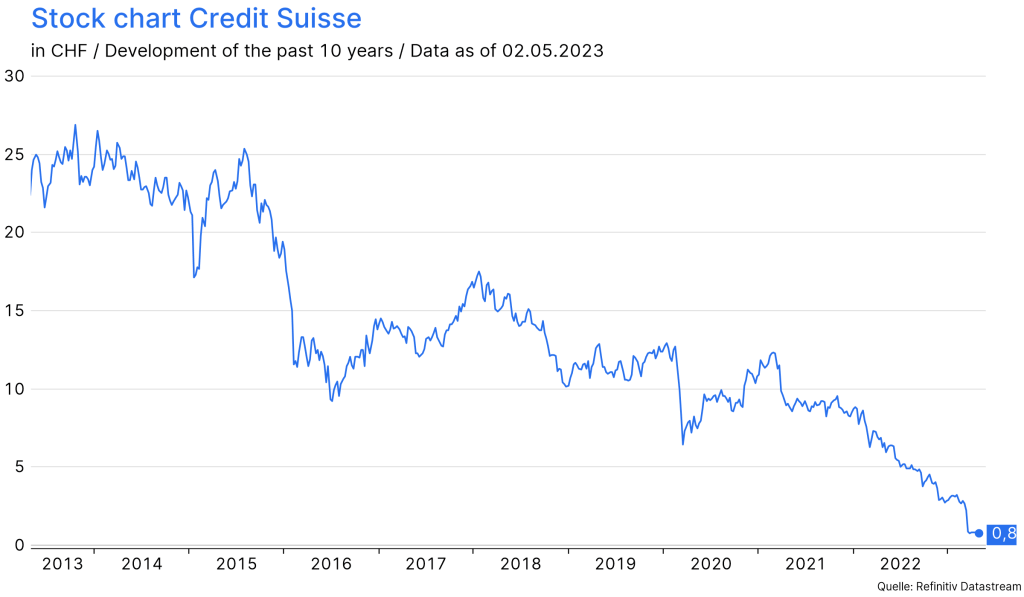

A few days later, the venerable Crédit Suisse came under massive pressure. A series of scandals included a casually worded remark by the major Saudi shareholder, who made it clear that he would not make any further investments in the bank. This led to a veritable sell-off in the share price.

The Swiss National Bank then pumped generous liquidity aid into the stumbling bank, which stabilized the share price in the short term. Orchestrated by the Swiss National Bank, however, a merger with rival UBS was being worked on, including federally secured liquidity loans, which was made public the following weekend. Thanks to rapid action by the central banks, contagion risks to other institutions and a loss of confidence were contained.

The dangerous thing about bank runs

A glance at the history books shows that banking crises and bank runs are by no means a novelty of the 21st century and at the same time embody something bittersweet. True, they have always curtailed macroeconomic stability. But they also act as catalysts for great innovations and achievements. Above all, they help to make the system successively more robust, since without a solid banking system an economy would not be able to survive, and banks contribute a considerable share to sustainable economic growth.

As early as 1841, Charles Mackay recognized that Adam Smith’s construct of a rational “homo economicus” was a fallacy and that people move in irrational herds during economic bubbles and panics. It is this economic characteristic that makes bank runs so dangerous, as the foundation of a bank run is typically herd panic rather than imminent insolvency.

Now, if circumstances arise that cause confidence in the safety of deposits in financial institutions to wane, then it is rational for individuals to withdraw their deposits quickly. The faster one withdraws, the more of the invested capital one receives, the last ones receive nothing – a bank run occurs. However, if all deposits are withdrawn at the same time, insolvency occurs because not all loans can be liquidated quickly and without losses.

One have to leaf a little further through the history books to find the first actual banking crisis – Sweden in the 1660s. The Bank of Stockholm already knew how to use money deposited by customers to finance loans. In order to reduce maturity mismatches and to be able to make more loans, they made use of negotiable instruments of exchange. However, this led to the bank printing too many unsecured bills, which eventually led to the bank’s collapse. The bank was taken over by the state and Sveriges Riksbank (National Bank of Sweden) was founded as its successor.

Living la vida loca – the first emerging markets banking crisis

A leap across the North Sea to the United Kingdom of the 1820s, where London was just establishing itself as an international financial center. In search of more attractive real yields, it flirted with bonds issued by Latin American countries that had recently become independent from Spain, as so often at the expense of adequate risk assessment. When Spain was on the verge of default, panic spread and bonds lost massive amounts of their face values.

A spillover to British banks was inevitable and a bank run took its course. Insolvencies were the result and the Bank of England (BoE) prepared a bail-out package for teetering financial institutions as well as corporations – an absolute milestone in the fight against banking crises. In response to the collapse, the BoE completely remodeled the entire banking system and joint stock lenders were created, the ancestors of today’s mega-banks.

The birth of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve (FED) also has its origins in a banking crisis. Anno 1907 New York, where two local businessmen and owners of a number of banks, aggressively sought to expand their controlling interest in the United Copper Company. Greed coupled with misjudgment of the market and a falling stock price, caused the two to tap financial resources from their banking conglomerate.

Spillover to other institutions was inevitable and panic spread rapidly among investors. Interest rates shot up to 125% and, in the absence of a lender of last resort, J.P. Morgan engineered a bail-out for the remaining New York banks. However, the herd panic was already taking hold nationwide, leading to a massive tightening of the money supply in circulation. Financial stability was regained through, at the time, creative substitutes for cash. As a result of the crisis, the Federal Reserve System was established in 1913.

The Big Bang

The Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09 made “banking crises” or “bank runs” fully respectable. The list of insolvent institutions in that period is long. Excitingly, the first major victim at that time was not an American institution, but Northern Rock from the United Kingdom. There, the crisis of confidence, triggered by short-term liquidity problems, could no longer be solved by an emergency credit facility from the BoE, and the bank was eventually nationalized.

Bear Stearns, which refinanced itself by selling asset-backed commercial paper, had to file for insolvency within two days as its balance sheet total bled out from $17 billion to $2 billion. Only a takeover by JP Morgan Chase could provide stability here.

In response to the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09, the global banking system was made more stable through extensive regulations. For example, the limit for the necessary equity capital was raised in order to cushion losses in the event of rapid liquidation. The main focus was on the 30 largest banks, which are systemically important for the global financial system.

Conclusion

The turbulence of the past few weeks and months is by no means comparable to that of 2007-09. On the one hand, rapid action on the part of central banks minimized the risk of contagion, and on the other hand, banks have since been much better capitalized and credit quality has been many times higher. Consequently, the consequences for the real economy are rather moderate.

Comprehensive measures and government intervention are well justified to stem the downward spiral in a banking crisis. Historical as well as current examples underline that.

Banking crises and bank runs will continue to occur in the future, albeit in varying degrees of severity. As in the past, lessons will be learned from this crisis for the future so that the financial system becomes even more robust and stable in order to further reduce the damage to society in the event of future crises.

For a glossary of technical terms, please visit this link: Fund Glossary | Erste Asset Management

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.