States go bankrupt time and again. While the reasons for this can be manifold, the consequences of a state bankruptcy can also have both economic and political dimensions.

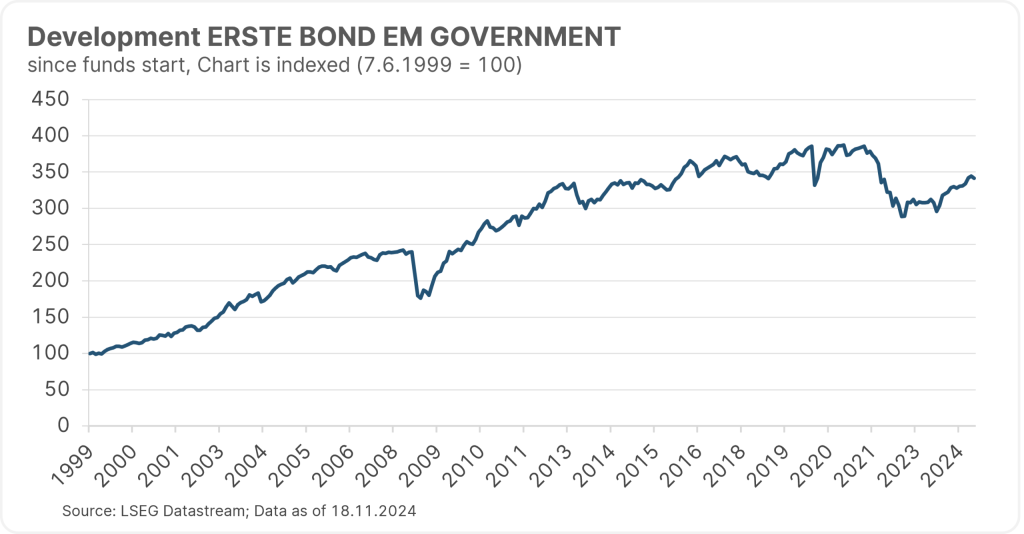

In this article, we take a look at the causes of sovereign defaults, the mechanisms involved in debt restructuring and the challenges faced by creditors and debtor countries. We also look at the role of debt restructuring in the fund management of emerging markets bond funds such as ERSTE BOND EM GOVERNMENT.

Can countries become insolvent?

The term insolvency refers to the general or momentary inability of an economic entity to pay its current liabilities and is generally applied to private economic operators.

However, a state is not comparable to a company and has different framework conditions. The state is not subject to any regulations under commercial or company law that define the existence of a situation of over-indebtedness or insolvency.

In the absence of such a definition, a state is usually said to be insolvent if it is permanently or temporarily no longer able to pay its foreign debts in foreign currency, as money in its own currency could be “printed” at will (albeit with catastrophic inflationary consequences). From a classic legal perspective, state bankruptcy is not actually possible, as a state cannot be liquidated.

State bankruptcies have a long history

In fact, a large number of states have stopped making payments or declared a moratorium over the past centuries. The list is long and goes back a long way: in 1345, for example, the English King Edward III refused to pay his debts to his Florentine bankers caused by the Hundred Years’ War. Or on September 30, 1797, the French finance minister declared all assignats and mandates (state securities) invalid and thus declared the state bankrupt.

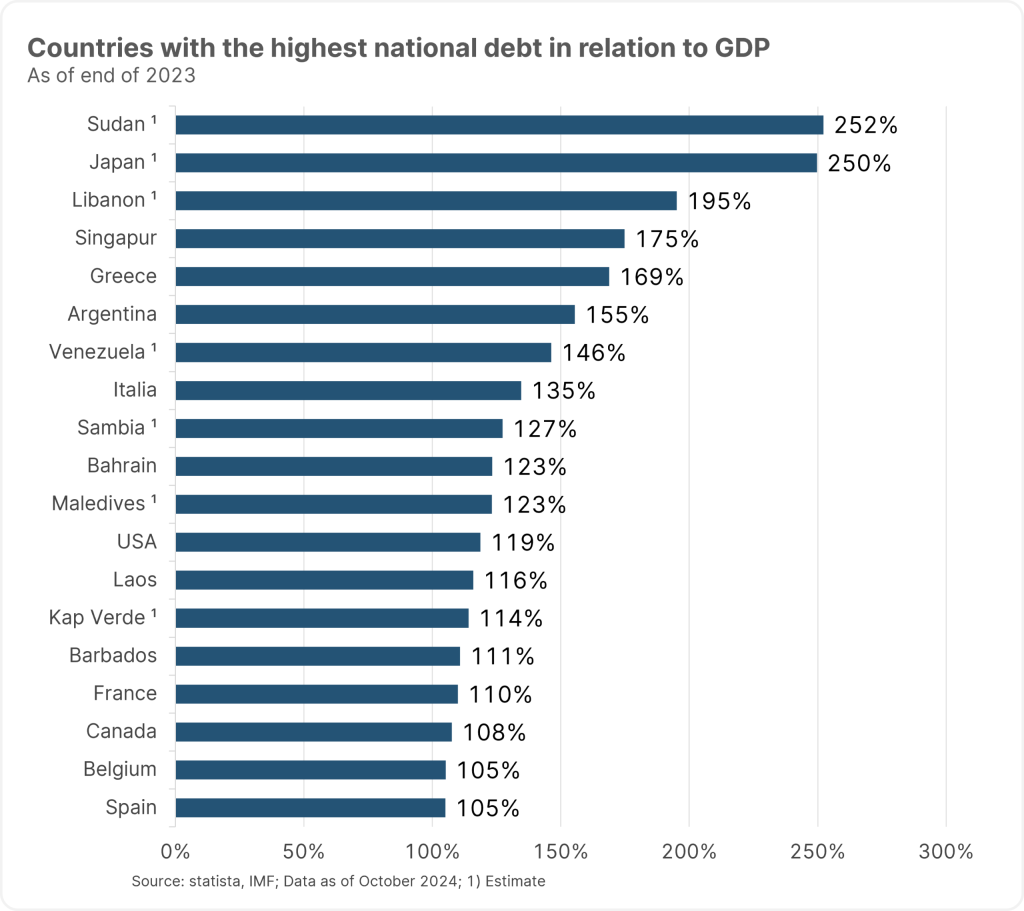

In 1918, the Soviet government refused to service the debts of the Russian Empire and in 1945, after the Second World War, Germany was bankrupt because Hitler had financed the war with the printing press. In recent history, with a few exceptions (e.g. Colombia), most emerging market countries have had to restructure their debt, either once or several times (Argentina). Very recent (2024) debt restructurings affected Ukraine and Ghana, for example. Sri Lanka and Pakistan are also expected to undergo debt restructuring measures in the near future.

What are the reasons for sovereign defaults?

In the vast majority of cases, especially in developing countries, the economic risk became apparent, i.e. a lack of foreign currency to service foreign debt. These countries want to, but are no longer able to: a question of ability to pay. If, on the other hand, governments no longer pay because they simply do not want to, even though they could (Russia in 1918) or no longer service their debts due to economic sanctions, for example (Venezuela), then these are cases of political risk. This is a case of “willingness to pay”.

At the end of the process, the liabilities are usually restructured. This can be “unfriendly” or “friendly”. In the unfriendly variant, the creditors are virtually forced to agree to the restructuring or otherwise remain stuck with claims that can no longer be realized. In this sense, the majority of cases are unfriendly. However, there are also states that “only” want to improve their debt structure, i.e. without any immediate economic urgency. Such sovereigns offer their creditors a voluntary (friendly!) exchange of existing debt for new debt instruments that are more advantageous for the debtor. In return, the creditors are offered some form of sweetener. An example of this is El Salvador in October 2024.

Debt rescheduling

The ultimate aim of any debt restructuring is to relieve the sovereign debtor in order to put it back in a position to service its liabilities in accordance with the contract. In this respect, it is very similar to a bankruptcy process in the non-state sector. In one way or another, this relief always takes the form of a haircut, i.e. a debt waiver on the part of the creditors. In the vast majority of cases, this “haircut” takes the form of two options offered to creditors:

- A so-called “discount” variant: the creditor waives a certain part of his nominal claim right at the beginning. The interest rate on the new bond is in line with the market, usually variable. The term is longer than with the old claim.

- A so-called “par” variant: initially, there is no direct capital waiver. However, the haircut results from a fixed bond interest rate that is well below the market and a very long term (much longer than the discount variant).

Both variants have the same present value, i.e. discounted repayment stream. It is up to the creditor to choose which is more suitable for him. However, history shows a preference for the par option.

The accrued, unpaid interest (past due interest, “PDI”) is usually treated more favorably and securitized by:

- A so-called PDI bond. As a rule, the capital concerned does not fall victim to a haircut and the bond usually pays interest in line with the market, with a slightly shorter term.

Creditors are often offered a (very) small cash payment to motivate them to participate in the debt restructuring.

If you look at the sovereign debt restructurings of recent decades, you can see that the average capital waiver was around 40%. The debtor states are advised by specialized law firms and investment banks help with the capital market placement. A good deal…

Free rider problem

This occurs when a critically large group of creditors refuses to agree to the restructuring and thus prevents a successful conclusion for all. Their strategy is to obtain better debt restructuring conditions for themselves through special treatment. Argentina 2002 was such a case. However, contractual provisions in more recent contracts for international government bonds are now designed in such a way that such attempts at blackmail are largely prevented.

Other strategies in public debt management

Debt for equity swaps: Holders of foreign currency receivables are offered to convert their receivables into local currency with a certain nominal waiver and to capitalize a local company with the resulting amount. Example: Brazil.

Debt for nature swaps: The same procedure as for debt equity swaps, except that the local currency amount is invested in a defined nature conservation project. Example: Costa Rica and El Salvador.

Debt for Charity Swaps: Again the same approach, with the local currency amount being used for local charity projects. E.g. social housing. Here, the capital waiver for the investor is naturally 100%, as charity. Example: Mexico.

Are there other stakeholders in sovereign defaults?

The so-called “Paris Club”. This is the group of public creditors of the debt restructuring candidate. In other words, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, export promotion institutions of the creditor countries (e.g. OeKB) and the like. These creditors are given priority and therefore come first in the debt restructuring process. A successful conclusion of the negotiations with the Paris Club is a prerequisite for a debt restructuring of the so-called “London Club”. This is the large group of private creditors.

The investors

The greatest performance contribution for investors in emerging market debt securities, e.g. the ERSTE BOND EM GOVERNMENT bond fund, is generated:

1.) to recognize impending debt restructurings in good time by correctly assessing the economic AND (!) the political risk. Exposure on the books that is reduced too late would normally suffer considerable losses in value in the run-up to restructuring. And

2.) by re-entering the risk in good time in order to be able to take advantage of value increases resulting from a successful debt restructuring. These increases in value usually arise long before the debt restructuring is actually completed, as investors make assumptions about the restructuring conditions. As a result, the recovery value (RV = recovery rate) is estimated. If the market value of the securities to be restructured is below the RV, this could be a buy signal.

Note: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The performance is calculated according to the OeKB method. The performance assumes a full reinvestment of the distribution and takes into account the management fee and any performance-related remuneration. The one-off front-end load that may be incurred upon purchase and any individual transaction-related or ongoing income-reducing costs (e.g. account and custody account fees) are not included in the presentation.

A special case of a debt crisis caused by “hybrid” political risk is Russia after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. As part of the sanctions, trading in Russian government bonds was banned – external political risk. As a result, Russia only serviced its debts in roubles or not at all – internal political risk.

The market value of the USD 2042 bond, for example, plummeted from around 140% to around 20% after the attack and the announcement of sanctions. Despite Russia’s assurances that the massing of troops near the Ukrainian border was “only” an exercise and that there was no fear of an invasion, the fund management of ERSTE BOND EM GOVERNMENT reduced the Russia risk. The political risk was recognized in good time.

Notes ERSTEBOND EM GOVERNMENT

Please note that investing in securities entails risks in addition to the opportunities described above.

The fund pursues an active investment policy. The assets are selected on a discretionary basis. The fund is based on a benchmark index (for licensing reasons, the specific index used is stated in the prospectus, point 12 or the “Objectives” key information document). The composition and performance of the fund may deviate significantly or completely, positively or negatively, in the short and long term, from that of the benchmark index. The Management Company’s discretionary powers are not restricted.

Advantages for investors

- Broad risk diversification through the selection of bonds from a wide range of emerging markets.

- Foreign currencies are mainly hedged against the EUR.

- High earnings potential in the long term.

Risks to be considered

- Emerging markets are traditionally subject to high fluctuations.

- Increased risk due to the addition of issuers with medium to low credit ratings.

- Capital loss is possible.

- Risks that may be of significance for the fund are in particular: credit and counterparty risk, liquidity risk, custody risk, derivative risk and operational risk. Comprehensive information on the risks of the fund can be found in the prospectus and the information for investors pursuant to Section 21 AIFMG, Section II, chapter “Risk information”.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.