Interview with Prof. Dr. Ernest Gnan, Secretary General of SUERF – The European Money and Finance Forum and former Head of the Department of Economic Analysis at Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB). The opinions expressed here are purely personal and do not constitute official positions of OeNB or the Eurosystem.

What are the forecasts for economic growth in the coming months?

The most recent forecasts by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) published in September suggest a massive decline in economic growth across many countries. Russia’s economy is expected to shrink by 5.5% this year due to sanctions, but the other countries also suffer from the current situation; for example, Germany and Italy are expected to slip into recession next year. Also, according to the latest ECB forecast, instead of posting weak positive growth (+0.9%), the Eurozone could experience a recession (-0.9%) next year in an unfavourable gas and oil price scenario.

High prices are the main reason why companies and private individuals are increasingly experiencing financial bottlenecks. Will inflation rise even further?

The aforementioned slump in economic growth is happening at the same time as the massive rise in inflation. In its latest “World Economic Outlook”, the IMF is already making reference to a “cost-of-living crisis”. In the Eurozone, we are currently edging close to 10% inflation. Even inflation adjusted for energy and food prices reaches 4%. According to current forecasts, inflation will fall back to slightly above 2% by 2024. After all, if energy prices are already this high and do not rise any further, no further inflation will result thereof.

The main threat in connection with inflation now comes from so-called second-round effects. If, for example, wages rose very strongly, this would lead to a solidification of domestic inflation. Profit margins in the corporate sector also play an important role. And ultimately, any forecast is only valid on the condition that no further drastic unforeseeable events happen, for example at the geopolitical level – the recent OPEC decision to curb production volumes being an example of such events.

Surely these forecasts are fraught with a certain degree of risk?

That is correct; a long war in Ukraine and energy-rationing among companies and private households could exacerbate bottlenecks on the supply side and at the same time further erode trust and thus demand. There is also massive upward pressure coming from wages, as the current wage negotiations show. Inflation, initially only driven by energy, has been spilling over to other areas at an increasing rate. Cost pressures on companies have increased: in Germany, for example, the input costs for production have risen by almost 150%. With a delay of a few months to a year, this is also eating into consumer prices.

How does the currently very high inflation influence inflation expectations?

It is crucial for the monetary policy that people are firmly convinced that the ECB will bring inflation back to the 2% target. If this were not the case, the ECB would have to tighten the monetary reins all the more to dampen inflation again – at a higher cost in terms of economic growth and employment. Currently, surveys show that the public is confident that inflation will be brought back to around 2% by 2024. The longer inflation remains very high, the greater the risk that confidence will fade, having inflation expectations slide upwards. It is now important for the ECB to maintain and justify this confidence through clear interest rate signals. At the same time, it is clear that the current situation is very challenging for the monetary policy: it is quite painful and may also be unpopular to normalize it in a looming recession.

“It is quite painful and may also be unpopular to normalize monetary policy in a looming recession.”

– Prof. Dr. Ernest Gnan, Secretary General SUERF – The European Money and Finance Forum

Were the forecasts by the central banks overly optimistic?

At hindsight, no doubt they were. But it has to be said that in recent years we have experienced events that the central banks – or other experts and observers, for that matter – simply could not have predicted. We are dealing with massive “serial shocks” here: the global financial crisis, the euro government debt crisis, the Covid crisis, and now Russia’s war against Ukraine with the resulting sanctions. The past three years have massively damaged international production chains and increased the cost of energy, raw materials, and intermediate goods. Wars always cause inflation. The aforementioned OECD forecast is therefore aptly titled “Paying the Price of War”.

The consequence of these shocks is that the state intervenes ever more deeply in the economy. Short-term understandable band-aids take precedence over long-term structural adjustments. This is most obvious in energy: Russia’s war has in some ways caused us to find ourselves in the middle of a disorderly energy transition. The high energy prices threaten to cripple production while weakening purchasing power and demand. For an energy-importing country such as Austria, this means a massive, potentially permanent loss of welfare. The only way out is a determined strategy forward towards the expansion of renewable energy and the diversification of our foreign trade relations.

Where does the monetary policy lead us?

Until 2019, interest rate hikes and cuts by various central banks around the world have roughly been on par. In 2020, central banks around the world cut interest rates in response to the pandemic, and now we see significant rate increases from almost all central banks in response to global inflation. For investors, this means that diversification across countries is not working well at the moment. The US Federal Reserve is targeting a Fed funds rate of over 4% for the end of 2022. In 2023, US interest rates are likely to go up a bit further. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s message was remarkable: restoring price stability will require monetary tightening to last for quite a while.

The ECB will also continue to raise key interest rates in the next monetary policy meetings, as ECB President Lagarde announced in September. At the same time, however, it is important to bear in mind that the interest rate increases are taking place from an extremely low level and that the ECB’s monetary policy is currently still far from “restrictive” – rather, we can see a normalisation of the monetary policy.

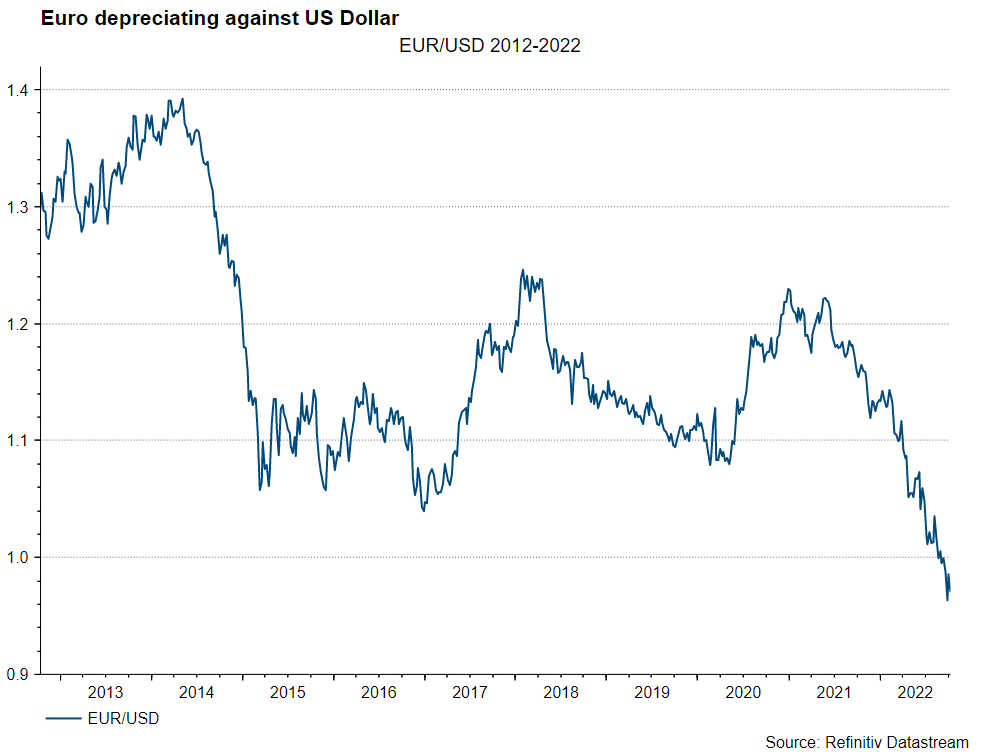

What does all this mean for the value of the euro vis-à-vis the US dollar? Do you expect the euro to fall further?

There are only two things I can say about the exchange rate: the euro-dollar exchange rate has been within a bandwidth of 0.80 to 1.60 in all the years since the euro has existed. The strong exchange rate fluctuations reflect economic fundamentals such as growth, inflation, and interest rate differentials as well as external imbalances or expectations about them. The market momentum and political factors also play an important role, such as the global status of the US dollar as a reserve currency or the role of the Swiss franc as a safe haven in times of crisis.

Central banks are generally very cautious about making statements regarding the exchange rate – it is not a target for monetary policy, not even an intermediate one. It is only relevant to the extent that it can influence domestic inflation – for example, the weak euro exchange rate is currently increasing inflationary pressure in the Eurozone, e.g. through higher energy prices (which are often invoiced in US dollar). The number of factors influencing the exchange rate defies modelling, which means that ultimately there is no economic model that forecasts the exchange rate better than a simple random generator.

For a glossary of technical terms, please visit this link: Fund Glossary | Erste Asset Management

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.