What goals is the ECB pursuing?

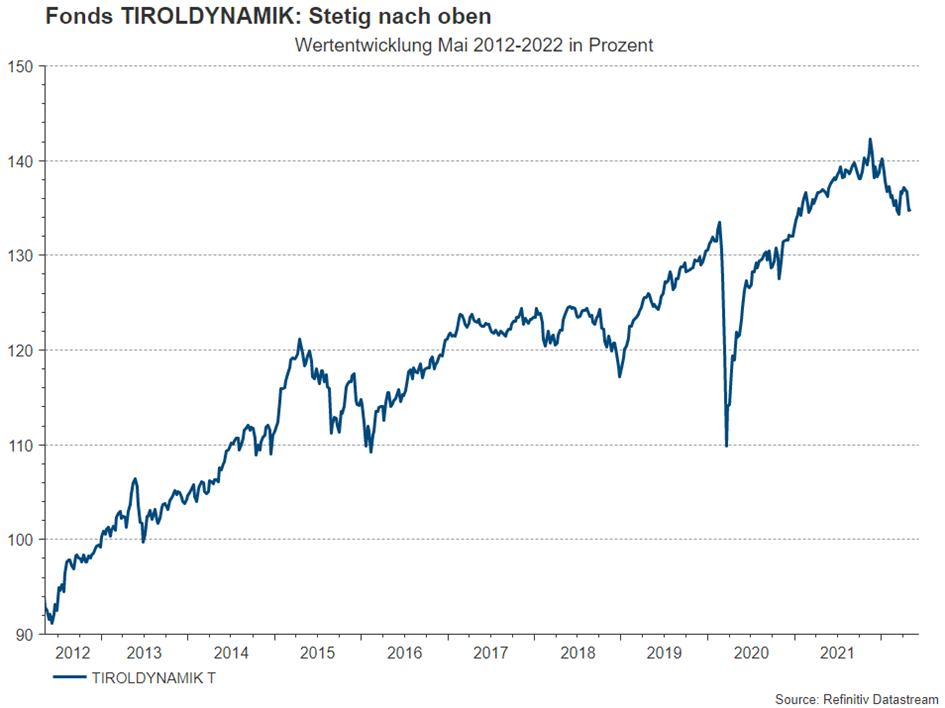

Since the Great Financial Crisis (2007 – 2009), one would have been forgiven for thinking that the central banks are constantly extinguishing fires while also caring about inequality, climate change, house prices, financial market stability, being lender of last resort, and geopolitics. So-called “woke” central banks, however, have the tendency of disregarding rising inflation[1]. Central banks have been granted independence so that they can focus on a clearly defined task. As long as inflation was low, forays into uncharted territory would be tolerable. However, in Austria, at 7.2%[2] the rate of inflation was as high in April as previously in 1981 (please see fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Consumer prices Austria, y/y in %

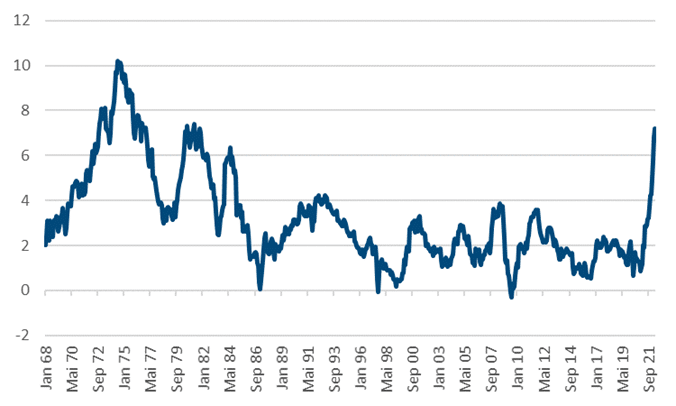

Fig. 2 illustrates how broad the increase in consumer prices has been in the Eurozone. Almost all main components have contributed positively in the past 18 months.

Fig. 2: Harmonised CPI, Eurozone

There are different kinds of price stability

Price stability is a basic requirement of a market economy. As the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Art. 127, paragraph 1) clearly states: “The primary objective of the European System of Central Banks (hereinafter referred to as ‘the ESCB’) shall be to maintain price stability. Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ESCB shall support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union. […].”

Price stability means 0% inflation. The European Central Bank (ECB) has gradually softened up this definition. Even prior to the introduction of the euro, the later (and first) ECP President Wim Duisenberg understood 2% to be the tolerable upper limit[3]. The “slightly below 2%” phrase was later developed on the basis of said 2% mark. It turned into a real goal under Mario Draghi in 2015: “We shouldn’t forget that our mandate is price stability, price stability defined as keeping inflation rate close but below 2%.”

With the statement on its monetary strategy of 2021, the ECB further softened price stability: “The Governing Council considers that price stability is best maintained by aiming for two per cent inflation over the medium term. The Governing Council’s commitment to this target is symmetric.”

President Lagarde explained this to the international press in the following terms: “The new formulation removes any possible ambiguity and resolutely conveys that 2% is not a ceiling.”

We can assume that the signatories weighed the pros and cons of a little inflation vs. deflation very carefully when wording the Maastricht Treaty. Ultimately, the Treaty was signed by the EU parliaments. They dictated the goal of price stability, i.e. 0% inflation. The ECB Council, an executive body, has no legitimacy to amend this goal.

Expansion of the money supply to finance government debt?

After the insolvency of Lehman Brothers, the ECB, as perceived saviour of last resort, generated endless money supply growth (SMP, OMT, PSPP, LTRO, TLTRO und PEPP). The central bank money supply (monetary base, M0) increased by a factor of 7x from August 2008 (on the eve of Lehman’s bankruptcy) to March 2022 (fig. 3)[4].

Fig. 3: Development of monetary aggregates in the Eurozone

After the collapse of the interbank market in 2008, the ECB came to the rescue and let its member central banks grant the commercial banks in the various economies money at low rates almost without any limits. This full allocation policy remains in place to date. From 2010, the ECB started urging the national governments to implement bailout packages as it was worried about massive write-down losses due to non-performing loans in the periphery, which were also only backed by government bonds that were on the verge of defaulting. Due to this decision by the ECB the parliaments came under significant pressure to make a decision. France wanted to infringe with the clauses of the Maastricht Treaty and threatened to leave the EU. As the then French Minister of Finance, Christine Lagarde, conceded: “We violated all the rules because we wanted to close ranks and really rescue the euro zone.”

Decentralised printing press

We really have to call that situation a “decentralised printing press”, with several national central banks avoiding the Frankfurt-based ECB in their efforts to up their liquidity, notably via ELA loans and ANFA assets, for example. The latter were kept secret for a long time. Until 2014, Ireland even violated the upper limits as set by the ECB in the Agreement on Net Financial Assets (ANFA). According to the consolidated figures of the euro system as of 22 April, the book values of these assets amounted to EUR 1,676bn, or 19% of the balance sheet total.

During the corona crisis, all floodgates were opened. In her first press statement on 12 March 2020, ECB President Christine Lagarde said about Eurozone government bond spreads that it was not the task of the ECB to do away with spreads. Since this was not appreciated by the capital market, the ECB announced the first tranche of the PEPP worth EUR 750bn on 18 March 2020, with two further to follow.

With all its bond purchase programmes, the ECB has helped the various governments to go further into debt over the past (almost) one and a half decades. The memorandum of the former governors also highlights the dubious legitimacy of the asset purchases in light of Art. 125 of the EU Treaty[5]: “There is broad consensus that, after years of quantitative easing, continued securities purchases by the ECB will hardly yield any positive effects on growth. This makes it difficult to understand the monetary policy logic of resuming net asset purchases. In contrast, the suspicion that behind this measure lies an intent to protect heavily indebted governments from a rise in interest rates is becoming increasingly well founded. From an economic point of view, the ECB has already entered the territory of monetary financing of government spending, which is strictly prohibited by the Treaty.”

Art. 5 paragraph 2 of the EU Treaty also suggests that the ECB has arrogated competencies beyond its mandate: “Under the principle of conferral, the Union shall act only within the limits of the competences conferred upon it by the Member States in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein. Competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States.”

Hans-Werner Sinn worded it in a particularly pointed way[6]: “In the Treaties, the ECB has not been given the right to grant interest payments on a country-by-country basis or to accept the resulting target balances, and if it has not been granted the right explicitly, it certainly has not been granted the right by the principle of conferral, which applies to all EU Treaties (Art. 5, paragraph 2 of the EU Treaty).”

The government bond purchases reduced the interest rates payable by states and triggered more government debt. However, the ECB undermines its independence that way: if members states have high levels of debt, they will think twice nominating monetary falcons as central bank governors, who largely pursue the goal of price stability.

Unstable status quo and imminent danger

On the real estate markets and in the construction industry, prices have been rising significantly for a while (reduced working hours, lockdowns, material shortages). The perturbed supply change extended the delivery times for industrial intermediate products, which also expanded the waiting time for final products amid a demand backlog. The expansive fiscal policy generates demand effects although the economy in the Eurozone has been in recovery mode since the first year of corona in 2020. The energy transformation leads to rising prices. Baby boomers are retiring, which boosts inflation. And then there is the depreciation of the euro. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia has also fuelled energy prices. The increase of producer prices of more than 10% in summer 2021 should have been a warning signal.

ECB has to tighten monetary policy

The ECB has to start tightening the monetary policy as soon as possible and learn a lesson from the Fed. An increase in interest rates would induce states to be more disciplined about debt again. Quantitative tightening is necessary. The decentralised creation of money (e.g. ANFA and ELA) should be terminated, because this situation causes a set of redistributions across countries with externalised inflation risks that are not politically legitimised. The central banks should return to short-term refinancing facilities against high-quality collateral. The long-term interest rates should be set by the markets, otherwise the stability of a federation of states is in danger if a member state gets into excessive debt without having to pay higher interest rates. The ECB Council does not have the mandate to anticipate the fiscal union.

„The ECB has to start tightening the monetary policy as soon as possible and learn a lesson from the Fed.“

Roman Swaton, Head of Credits, Erste Asset Management

© Photo: Huger

Up until very recently, the expansion of the money supply had very limited effect on economic activity (liquidity trap). The money was hoarded rather than flowing into the cycle of goods. The banks were hesitant in creating deposit money (N.B. the latter creates additional money supply via commercial banks with the goal of providing more liquid funds to the customers). However, the money supply overhang is a ticking time bomb, where one has to hope it will not also lead to accelerated M1 growth. The trust in the value of money has to be preserved. There are enough examples in history that exemplify the dramatic societal consequences of inflation. Having strayed from its original mandate, the ECB has to take even more pronounced steps now.

[1] „Too much to do“, Special Report: Central Banks, The Economist, 23.04.2022, S.7 quotiert Larry Summers, Harvard University (former Secretary of State at the US Treasury)

[2] “Inflation forecast at 7. 2% in April 2022 according to flash estimate”, Statistics Austria, Press release 29. 04. 2022

[3] “The Miraculous Increase in Currency“, H.-W. Sinn, Herder 2021, p.257

[4] On the basis of the quantity theory of money, all else being equal, this would also lead to an increase in the level of prices by a factor of 7x. Supporters of this theory generally monitor higher money supply aggregates such as M3. In its initial years, the ECB also pursued an annual M3 growth target of 4.5% (3M moving average).

[5] “Memorandum on ECB Monetary Policy”; H. Hannoun, O. Issing, K. Liebscher, H. Schlesinger, J. Stark, N. Wellink; Bloomberg News, 4 October 2019

[6] “The Miraculous Increase in Currency“, H.-W. Sinn, Herder 2021, p.81

Explanations of technical terms on investment and securities can be found in our Fund Glossary: Fund Glossary (erste-am.at)

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.