The Spanish flu pandemic kicked off in late spring of 1918 as a moderately severe influenza outbreak at first. Only after the virus mutated during summer and returned much more virulent in the fall of the same year did a large number of people die.

Since the start of the current pandemic researchers and policymakers have worried about possible mutations of SARS-CoV-2. A recent paper based on over 18 500 virus genome samples collected thus far concludes that these worries are unfounded.

Viral mutations occur when errors are made in the replication of viral RNA during the infection. The process can be compared to making photocopies of building instructions for a chair. Sometimes the instructions get crumpled up, sometimes the photocopy machine is dirty or does not work properly so that in the end the copied building instructions are slightly different.

If the number of chair legs to be attached changes in the manual this could make the chair either more or less stable. Likewise, additions and deletions in the viral RNA can make the resulting virus more or less virulent.

At least 6 different strains of SARS-CoV-2

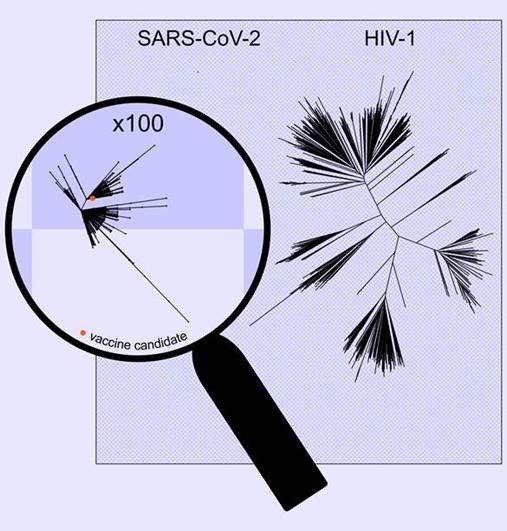

While researchers have identified at least 6 different strains of SARS-CoV-2, these strains do not show a large genetic variance. Unlike other pathogens like HIV or the influenza virus, the SARS-CoV-2 genome is rather simple, due to it being a single strand of RNA.

Sticking with the analogy above, its building instruction is contained in one big book and copying it therefore less prone to error compared to other pathogens where the building instructions are shorter but spread out across multiple books written in foreign languages. Furthermore, just like its predecessor SARS-CoV, the novel coronavirus appears to revert back to its original form as mutations appear to be less efficient at reproduction.

Furthermore, vaccines that were developed using the genetic information obtained in January 2020 will probably still be effective for the currently dominant variants of the virus. Most vaccines target the spike proteins on the virus’ hull that act like as key to the human cells it tries to infect.

There were only two observed mutations related to the make-up of these spike proteins and they had no effect on the ability of antibodies to bind to that area and render the virus ineffective.

Image: genetic family tree where branch length accounts for genetic divergence

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.