Mikuláš Splítek

Author: Mikuláš Splítek, Fund Manager

It is a wonderful situation for a stock picker when a factor is important, knowable, and overlooked. Assessing managers’ character is clearly important. On the one hand, it is about avoiding errors like frauds, theft, disastrous acquisitions and toxic culture. On the other hand, businesses are communities of people, and those that survive and prosper are those that customers, employees, and suppliers want to be a part of. It is often overlooked too. Due to its elusive nature, there is no standardized way to judge someone’s character; the topic rarely appears in textbooks or professional courses, and investors are generally skeptical about their ability to asses it. Which leads to the following question: Is it knowable? In other words, is there some reliable way to judge someone’s character?

Some investors deem it impossible. They avoid contact with management altogether to bar themselves from biasing their judgement of the business. To me, they overestimate their ability to forecast financials and underestimate the role of people. After all, it was people who drove financial results, not the other way round. Think of Berkshire Hathaway in 1960s when a new CEO took the reins – it was not the economics of the textile industry that determined the outcome. It is true that Warren Buffet, Berkshire’s CEO, also said: “When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.” but, so far, people are the only creative force that can alter the course of business (even though occasionally the best option might be to liquidate it – as in case of Berkshire’s textile operations).

The oracle Of Omaha

The fact that judging managers’ character is possible, at least for some, should be apparent from comments that successful investors make upon the topic. “We lend money on character,” J. P. Morgan said famously during the Congress hearing in 1912. “He had no background in insurance. I just liked the guy,” admitted W. Buffett in his biography, talking about his now-star manager Ajit Jain. “I think if you asked me this question 25 years ago, I would have had a reasonably long list of things. Today, I’m absolutely convinced that there is nothing more important than being partners with great people,” replied Yale Endowment manager David Swensen when asked about cornerstones of investing. They all seem confident in their forward-looking judgement on manager’s integrity. To them, such an assessment is doable.

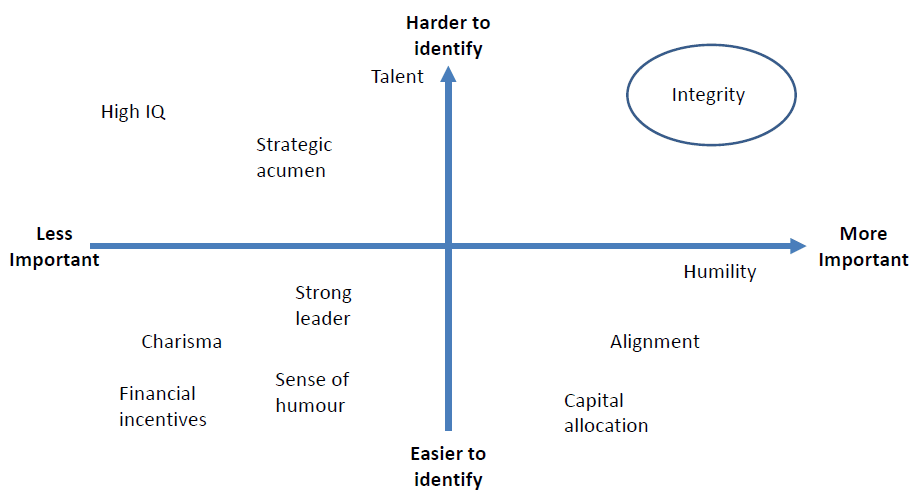

That does not mean it is easy. Managers rarely volunteer disclosing negative information unless they absolutely must, and it is difficult to separate management character from their professional skills. After all, everyone has at least some positive attributes, and managers – for both good and bad – self-select for good salesmanship. There is also a societal taboo against talking about people in the negative. Further, management meetings tend to occur in a prearranged environment with a fixed script which constrains closer interchange. No wonder, due to these facts, many investors still find other managerial capabilities (leadership, capital allocation, strategic acumen, alignment, etc.) easier to identify, as depicted on the chart below.

Quelle: Vinall, R. (2017). Identifying Managers with Talent and Integrity. Omaha, 5th May.

You can explore many sources of information – time series of annual reports, conference calls, management meetings, former employees, competitors and suppliers’ contacts, company biographies – and still remain puzzled about managers’ character. In media, we witness cases of very skilled and intelligent people (analysts, investors, business partners) being tricked by dishonest managers over and over again. These cases only fuel the already mentioned skepticism about the ability to judge managers’ character on one (and much larger) side of the investment community. On the other side there are a handful of individuals who deem it not only possible, but inseparable and an almost natural part of the investment profession (Buffett has a near 100% track record in picking his managers). Why is there such a wide rift?

How do you master the ability to pick character?

Well, perhaps because this ability is hard to get – it cannot be taught. You can master financial modelling or technical analysis quite quickly, and to the large extend without changing your own personality. In computer jargon, it is like adding a new application. But judging someone else’s character correctly is different. It is more like an operational system upgrade. It seems directly linked to your own personality. You have to live by the values you seek in the managers to know what those values are. You have to be morally apt in order judge other people morals. After all, we like people who are similar to ourselves, so only after you yourself escape a shade of moral mediocrity you can discern exceptional or poor characters. Only then you can harness liking or disliking to your advantage. In other words, you have to raise yourself higher to see further. And this is not quick, nor smooth. No one can teach you that. Virtue cannot be taught – argued Plato in Meno more than 2,300 years ago. But it can be learned. It can be learned – borrowing words from Viktor Frankl and Carl Rogers – via genuine and unrelenting responsiveness to life.

Summing up, to judge managers’ character correctly you have to become a good person yourself. As there is no universal definition for ‘goodness’, the best you can do is to try. Of course, you will never know if you got it right, but that is not necessary. Progress will be made. Most of the people will find this prescription too vague to even try, and thus, if you persist, you shall get a competitive advantage. It might appear counter-intuitive that strive for good can help in the world of financial markets, but I reckon that’s exactly why only a handful of people outperform constantly.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.