The economic implications of Brexit

Opinion polls and betting odds as well as the muted response of debt and equity investors suggest that Brexit – the UK’s exit from the EU – is not the most likely scenario. That said, it cannot be ruled out. For example, about a quarter of all opinion polls conducted in the UK since last autumn resulted in a majority for the leave-vote and there are some signs that the leave-faction is gaining ground as we pointed out in our previous blog on this topic.

The IMF and others (e.g. recently Barry Eichengreen) have warned that the economic and political repercussions of Brexit would be highly negative – which is reason enough to take a closer look at its implications for the UK and for Europe.

1. How will Brexit affect the UK economy?

The EU is Britain’s most important trading partner, accounting for 45% of UK exports in goods and services, and 53% of its imports. It is estimated that 3.5 million jobs in the UK are linked to exports to the EU. Moreover, about a third of immigrants in the country are originally from other EU countries. In a nutshell: Economic relations between the UK and the EU are intense, and any steps of dis-integration will likely have a serious impact.

The bulk of all studies that dealt with the implications of Brexit clearly suggest that the UK economy will suffer. The negative impact will mostly come from

- falling trade in goods and services between the EU ex Britain (EUx) and the UK;

- a drop in foreign direct investments in the UK;

- shrinking labor supply due to restrictions on migration (which is one of the political core issues of the ‘leave’-campaigners); and

- rising uncertainty that will likely weigh on both consumer and investment demand.

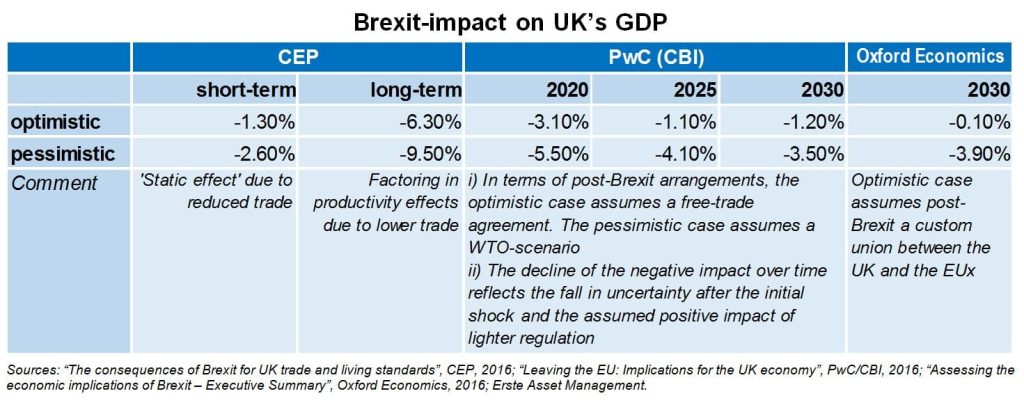

However, quantifying the impact of any of those channels as well as the overall impact of Brexit is subject to massive uncertainty. Estimates in recent studies by the Centre of Economic Performance (CEP), PwC (commissioned by CBI, the Confederation of British Industrialists), and by Oxford Economics range from close to zero to a negative impact of -9.5% on the UK’s GDP. Earlier studies, some of which were not focusing on the specific event of Brexit but on the general issue of UK’s EU membership, imply an even wider range of outcomes.

2. Which factors will affect the UK economy positively in case of Brexit?

While the majority of studies suggest that Brexit will be harmful for the British economy, the negative effects might be partly compensated by two factors: (a) fiscal savings due to the elimination of UK’s contribution to the EU budget, and (b) the escape from Brussel’s overzealous regulatory regime in many areas.

Both effects, however, will likely be small.

- The UK contribution represents just 0.5% of the country’s GDP. While this will be saved in case of Brexit, the expected drop in GDP plus a possible fiscal expansion to mitigate Brexit’s negative impact on the economy will likely erase any fiscal gains. Moreover, it needs to be noted that there is a high chance that the EUx will again request again a contribution from the UK as a price for a post-Brexit trade agreement.

- Freeing the UK from the EU’s regulatory burden is one of the few economic arguments supporting the case for Brexit. However, as Simon Johnson recently pointed out, the UK in terms of product and labor market regulation is closer to the US than to Western Europe. The country already ranks number six worldwide in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2016 report. There is always red tape that can be removed, of course, but there is little evidence that the EU’s regulatory framework hindered the UK in pursuing a relatively liberal regime. Hopes that further deregulation will turn out to be a huge support for further UK economic growth, levelling the negative impact from lost trade, may prove elusive.

3. Why is there such a wide range of estimates?

The US author William G. Simms once famously stated that “economists put decimal points in their forecasts to show that they have a sense of humour.” Some of the estimates, like the one of a negative GDP impact of -0.1% over a period of one-and-half decades, seem to confirm his dictum.

Equally noteworthy, however, is the wide range of estimates between the various studies, but also within single studies. The main source for these discrepancies is that nobody knows how the post-Brexit arrangement between the EUx and the UK will look like – probably the most salient ‘known unknown’ in the whole story.

Following Brexit, the EUx and the UK would have a time-span of two years (during which the status-quo would remain) to agree on a new trading regime. Given the importance of their trade and other economic relations, both sides will have a strong interest in finding a compromise. In practice, however, there is a variety of options, ranging from far-reaching agreements like the one between the EU and Norway (which, for example, includes a contribution of Norway to the EU budget) to a simple customs union like the one between the EU and Turkey. Alternatively, EUx and the UK could revert to the fallback option of trading on WTO/Most Favored Nation-terms, which would not require any special arrangements, but would generally dampen the trade relations between the two partners and would, over time, lead to growing non-tariff barriers (see the overview here).

Other factors (in addition to assumptions about a post-Brexit trade regime) that are responsible for divergent overall estimates are the expected impact of rising uncertainty and the supposedly positive impact of lighter regulation. Both factors are difficult to model.

Rising uncertainty post-Brexit will affect the economy both through its impact on private demand, particularly investment demand, and via its impact on financial markets. It will likely raise risk premiums, thus affecting all asset markets, and could make it more difficult for the country to finance its substantial current account deficit, as the Bank of England recently warned.”

4. What will be the fallout on the European Union ex Britain

The fallout from Brexit would not be confined to the UK. The rest of Europe would also suffer, although the economic consequences would be less pronounced. The UK accounts for roughly 16% of EUx goods exports (2014), making the UK the single biggest market, even ahead of the US (15%), and twice as big as China (8%). Estimates spread in the media suggest that about two million jobs in the EU are linked to trade with the UK. Almost all European partners, particularly Germany, run substantial trade surpluses vis-a-vis the UK, while the balance in services is typically negative.

According to recent estimates from sell-side research (JPM, The impact of Brexit on the (rest of) the EU, Economic Research Note, Feb 19, 2016; ING, Damage from a Rollong Stone, March 23, 2016) Euro area growth could suffer by 0.2-0.3 percentage points over the next 18 months following Brexit (JPM) or between 0.1-0.5 percentage points by end-2017 (ING). This does not look dramatic, but given Europe’s lackluster growth outlook (consensus 1.5-1.6% in 2016 and 2017) and an unemployment rate north of 10% any slowdown would be highly unwelcome.

The fallout on Europe will be unevenly distributed. Three countries in Europe with particularly close links to the UK stand out: Ireland, Cyprus and the Netherlands. While Italy, Croatia, Bulgaria as well as Austria are among the countries least affected according to a study by the Gobal Counsel.

It has been argued that in the long term Europe may even benefit from the UK’s departure. First, the UK has taken a disproportionally high share of the EU’s inward foreign direct investment (FDI), and in case of Brexit continental Europe might be able to attract a bigger share of the pie. Secondly, a more difficult access of UK financial firms to the EUx internal market “might set in motion an import substitution process which may eventually benefit at least some EUx member states.”

There is general consensus that the really dangerous fallout from Brexit will not happen in the economic but rather in the political sphere. Brexit would be the first setback for the European project that, so far, has been moving only in one direction: toward regional expansion and closer economic integration. This process has not been without frictions and sometimes came to a standstill, but so far has not been reversed.

UK’s choosing to give up her membership would have a number of implications for Europe and the world:

- It would change the internal balance in the EU between, to put it crudely, more market oriented Northern countries (incl. the Netherlands and Sweden) and a more statist Southern block (incl. France and Italy), with Germany somewhere in the center.

- It would weaken Europe’s standing in a global context, given that the UK (together with France) has been one of the most active players in geopolitical affairs among all EU members.

- It would also weaken Europe’s military capabilities, as the UK has the most advanced defense sector within the EU. At a time, when the US interest in European affairs seems to be waning as well – as some commentators have argued – a weaker Europe in terms of military presence will have geopolitical repercussions.

- Finally, and probably most importantly, Brexit might turn contagious. The assumption is that in the wake of Brexit, centrifugal forces – represented by nationalist right-wing parties in some European states or separatist movements in Spain and elsewhere – would gain momentum.

Bottom-line: Brexit will most certainly have profound economic and political consequences both for the UK and for the European Union. Unsurprisingly, financial markets have already responded to the uncertainty created by the referendum and a more pronounced reaction is likely in case Brexit really happened – which will be the topic of the next blog in this series.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.