2017 has been another bumper year for global equities with the MSCI All Country Index gaining ca. 18% in the first ten months in dollar terms. November, however, has not started well for risky assets.

European equities lost 2.9% in the first half of the month, US stocks were flattish, corporate risk spreads widened, and the VIX, often seen as “Wall Street’s risk gauge”, has started climbing after hitting historical lows in October. Not any of these developments suggest that something dramatic is going on. The setback was most likely a response to growing political tensions in the Middle East and the related oil price hike as well as to uncertainty about US tax reform.

Still, considering that the equity cycle is long in the tooth, valuations across all assets are rich and stock market volatility has been suspiciously low, it is reasonable to ask whether the backdrop for stocks is deteriorating as we are approaching 2018.

The main factors that supported international equity markets at various times during or throughout the year were

- a broad-based global recovery, with all 40+ economies tracked by the OECD showing positive growth

- the continuously benign monetary policy backdrop

- a strong earnings outlook across all major regions

- hopes for policy reform in the US and in Japan

- abating Chinese risks, and

- growing confidence that populists– despite their rising political influence in core Europe – will not be in a position to dismantle the European project.

None of these factors have significantly changed over the past few days and weeks. Particularly global growth will likely remain robust; monetary policy moves – while clearly showing a tightening bias – are taken with extreme caution and have been well communicated to investors; and consensus expectations point to another positive earnings performance in 2018. Thus, there is hope that the recent weakness in international markets may turn out to be just a temporary blip.

Valuation: Rich, not bubbly

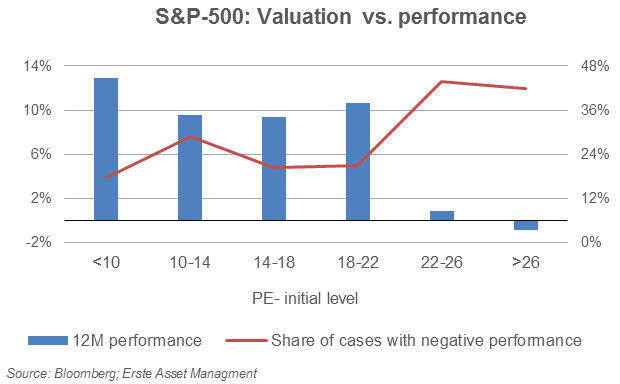

Valuation remains a concern. By historical standards equities are expensive, particularly in the US. However, multiples are still not in bubble territory. More importantly, in itself, valuation is seldom a trigger for a correction. For example, as the chart below shows, only when the market’s price-earnings-ratio (PE) moves towards the mid- and high-20s, historically US stocks turned in a flat or negative performance over the subsequent twelve months. Surprisingly, at PEs of 22 or lower, the performance over the following twelve months was broadly unrelated to valuation at the beginning of the period.

At present, the S&P 500 is trading on 21.6 times trailing earnings, which is close to but still outside the danger-zone. Moreover, while “this time is different” is often a very dangerous argument, the current macroeconomic backdrop in terms of r-star (the natural rate of interest) and the growth outlook could justify a market valuation well above historical levels, although still lower than its current level (see Lansing, K.J, Stock Market Valuation and the Macroeconomy, FRBSF Economic Letter, 2017-33, Nov. 13, 2017).

Reasons to be cautious

While neither top-down fundamentals nor valuation are really raising alarm-bells, there are still a number of reasons to be more cautious going forward:

Growth disappointment. While global growth has surprised to the upside in 2017 and the outlook for 2018 remains positive, a further acceleration in 2018 is unlikely. Europe and the US are already growing above potential, and growth in China and Japan is expected to slow. Moreover, expectations regarding the economic newsflow have been lifted in response to the flow of incoming data, making further positive surprises less likely. Thus, growth surprises as a driver of earnings expectations and stock prices could be missing next year.

Excessive optimism. Investor surveys suggest that investors’ overall disposition is still very bullish. For example, according to the recent Fund Manager Survey of BoAML (“It’s frothy FAANG”, Nov 14, 2017), the share of institutional investors believing in a prolonged goldilocks-scenario of high growth/low inflation has strongly risen in the course of the year and is now at historical highs. There is clearly room for a rude awaking in case inflation should pick up in the course of 2018 and/or growth starts disappointing.

The end (of QE) is nigh. Probably the biggest risk is monetary policy. Even excluding the possibility of a policy mistake (like raising rates too fast), the very fact that the US central bank has started shrinking its balance sheet and the ECB will likely follow in 2019 is a source of uncertainty. While the key impact will be felt in fixed income markets, central banks’ tapering will have spill-overs to risky assets – either directly via liquidity effects or, indirectly, via its impact on risk premia (and therefore discount rates).

New risks. While markets have been surprisingly good in absorbing event risks (Brexit vote, Trump, Korea, Catalonia) over the past 18 months or so, it would be foolish to assume that this pattern will necessarily prevail going forward. A failure of tax reform in the US, a further rise of tensions in the Middle East, Italian elections, Spain’s handling of the Catalan situation, or a complete breakdown of ongoing Brexit negotiations – all of these events could trigger a prolonged switch into a risk-off mode.

Bottom line: The fundamentals for equities, which have markedly improved over the past twelve to eighteen months, still look good. Both economic and earnings growth remain supportive, but moving into 2018, the momentum will be receding and new risks are emerging. There is further upside for equities, but a replay of the strong 2017 performance is improbable and the odds of a correction are clearly on the rise.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Legal disclaimer

This document is an advertisement. Unless indicated otherwise, source: Erste Asset Management GmbH. The language of communication of the sales offices is German and the languages of communication of the Management Company also include English.

The prospectus for UCITS funds (including any amendments) is prepared and published in accordance with the provisions of the InvFG 2011 as amended. Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG is prepared for the alternative investment funds (AIF) administered by Erste Asset Management GmbH pursuant to the provisions of the AIFMG in conjunction with the InvFG 2011.

The currently valid versions of the prospectus, the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, and the key information document can be found on the website www.erste-am.com under “Mandatory publications” and can be obtained free of charge by interested investors at the offices of the Management Company and at the offices of the depositary bank. The exact date of the most recent publication of the prospectus, the languages in which the fund prospectus or the Information for Investors pursuant to Art 21 AIFMG and the key information document are available, and any other locations where the documents can be obtained are indicated on the website www.erste-am.com. A summary of the investor rights is available in German and English on the website www.erste-am.com/investor-rights and can also be obtained from the Management Company.

The Management Company can decide to suspend the provisions it has taken for the sale of unit certificates in other countries in accordance with the regulatory requirements.

Note: You are about to purchase a product that may be difficult to understand. We recommend that you read the indicated fund documents before making an investment decision. In addition to the locations listed above, you can obtain these documents free of charge at the offices of the referring Sparkassen bank and the offices of Erste Bank der oesterreichischen Sparkassen AG. You can also access these documents electronically at www.erste-am.com.

Our analyses and conclusions are general in nature and do not take into account the individual characteristics of our investors in terms of earnings, taxation, experience and knowledge, investment objective, financial position, capacity for loss, and risk tolerance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of the future performance of a fund.

Please note: Investments in securities entail risks in addition to the opportunities presented here. The value of units and their earnings can rise and fall. Changes in exchange rates can also have a positive or negative effect on the value of an investment. For this reason, you may receive less than your originally invested amount when you redeem your units. Persons who are interested in purchasing units in investment funds are advised to read the current fund prospectus(es) and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG, especially the risk notices they contain, before making an investment decision. If the fund currency is different than the investor’s home currency, changes in the relevant exchange rate can positively or negatively influence the value of the investment and the amount of the costs associated with the fund in the home currency.

We are not permitted to directly or indirectly offer, sell, transfer, or deliver this financial product to natural or legal persons whose place of residence or domicile is located in a country where this is legally prohibited. In this case, we may not provide any product information, either.

Please consult the corresponding information in the fund prospectus and the Information for Investors pursuant to § 21 AIFMG for restrictions on the sale of the fund to American or Russian citizens.

It is expressly noted that this communication does not provide any investment recommendations, but only expresses our current market assessment. Thus, this communication is not a substitute for investment advice.

This document does not represent a sales activity of the Management Company and therefore may not be construed as an offer for the purchase or sale of financial or investment instruments.

Erste Asset Management GmbH is affiliated with the Erste Bank and austrian Sparkassen banks.

Please also read the “Information about us and our securities services” published by your bank.