The semiconductor crisis has recently taken a turn for the worse again. The strong increase in global demand for semiconductors is being met by ever new supply problems on the part of chip manufacturers. The resulting supply bottlenecks are affecting numerous industries from car manufacturers, computer and cell phone producers to consumer electronics suppliers. The Ukraine war is now threatening to exacerbate the semiconductor bottleneck even further, because the country supplies around half of the neon gas crucial to semiconductor manufacture.

According to company spokesmen, the two Ukrainian companies Ingas and Cryoin have suspended their neon production following the Russian attack on their country. Ingas is headquartered in port city of Mariupol, which has seen particularly heavy fighting, while Cryoin is based in Odessa. according to Reuters news agency calculations based on data from research firm Techcet, between 45 and 54 per cent of the world’s neon production comes from these two companies alone.

The noble gas neon is needed for lasers used to expose silicon wafers in chip production. The manufacturers’ neon stocks are currently sufficient to keep production going for some time. However, should the war last longer, experts fear this could lead to a supply shortage of neon, further exacerbating the computer chip crisis.

Lockdowns in Asia and Earthquake in Japan Slow Down Supply Chain

The computer chip industry has been suffering from production shutdowns in Asia since 2020 due to lockdowns set into effect to contain the Corona pandemic. In addition, a harsh winter in Texas and a fire at a Japanese computer chip plant had caused supply chain bottlenecks in the previous year. In March, Japanese chip manufacturer Renesas also shut down three of its plants following an earthquake in Fukushima Prefecture.

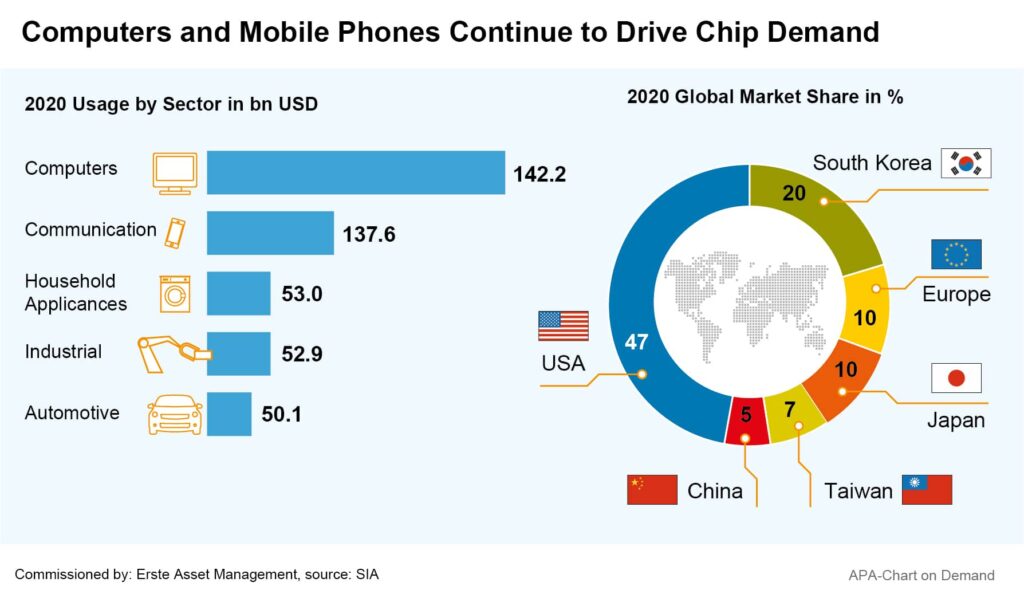

Meanwhile, demand for semiconductors continues to soar. The lockdowns during the pandemic accelerated the ongoing digitalisation trend: with the increasing adoption of home office work there came an increased need for laptops and cell phones, but also the need to expand the data centers running the cloud solutions required for this. In addition, the demand for entertainment consumer electronics products used at home during lockdowns also increased. This was followed by a rapid resurgence of automobile demand, which had temporarily slumped.

Soaring Demand Brings Record Sales, but also Capacity Problems

Booming computer chip demand brought semiconductor manufacturers record sales, but also pushed them to their capacity limits. According to the industry association SIA, sales in the global chip industry grew by more than 26 per cent last year to a record USD 555.9bn. Against this background, the world’s largest contract chip manufacturer and supplier to prestigious customers such as Apple- and Qualcomm, TSMC, reported a record quarterly profit to the tune of EUR 5.3bn for the period from October to December, an increase of sales by 24 per cent. Intel saw its revenue rise 3 per cent to USD 20.5bn in the same period, but the group’s quarterly profit decreased by 21 per cent to USD 4.6bn.

However, many computer chip manufacturers are now lagging behind the strong demand. “We are sold out until 2025, even 2026,” AT&S CEO Anreas Gerstenmayer recently told the German Handelsblatt. The Austrian semiconductor group is currently unable to accept any new orders.

The extreme globalisation of the production process is a double-edged sword for the industry: from the mining of raw materials to the finished and packaged computer chip, the entire production chain spans several continents – from the extraction of raw materials in mines in Africa and Asia, on to Japan, the US and Europe, where intermediate products and also the machines for manufacturing are produced, to the final chip production in Asian countries such as Taiwan, South Korea, China or Malaysia. But while the bundling of individual stations in certain locations allows a high degree of specialisation, strong economies of scale and thus low-cost production, it also makes the entire chain more susceptible to failures.

Malaysia is Becoming a new Hot Spot for the Chip Industry

Many chip manufacturers are therefore investing more heavily in new locations. Malaysia in particular is currently considered an attractive future location for the industry. Unlike the major computer chip manufacturing location Taiwan, which is being claimed by China less and less subtly, or South Korea with its proximity to North Korea, Malaysia is considered a place with relatively low geopolitical security risk.

AT&S started construction of a new plant in Malaysia in late 2021, with commercial operations scheduled to begin in 2024. The plant in Kumin, 350 kilometers north of the capital Kuala Lumpur, will employ 6,000 people to produce IC substrates. Intel has also announced plans to build a new computer chip manufacturing plant in Malaysia, planning to spend more than USD 7bn in the process. The plant is scheduled to take up operations in 2024. Intel has been manufacturing in Malaysia since 1972.

Intel Investing Heavily in the US and Europe

However, semiconductor manufacturers are also significantly increasing their investments in the US and Europe. Intel is said to plan to invest up to USD 100bn in Ohio for construction of a huge plant. The announcement is part of Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger’s efforts to regain its former dominance and reduce US dependence on Asian manufacturers.

In March, Intel also announced plans to build two semiconductor plants in Magdeburg, Germany, planning to invest USD 17bn. In addition, Intel plans to build a new research center in France and invest in Ireland, where the company operates its only European plant to date. Particularly in Ireland, Intel also wants to serve other chip companies in order to compete more strongly with the largest global contract manufacturers TSMC and Samsung. Further investments are planned in Italy, Poland and Spain.

EU Aims to Increase Europe’s Global Market Share to 20 Per Cent by 2030

In light of the semiconductor bottlenecks, the EU is currently pushing to expand semiconductor manufacture in Europe, in part to make key chip customers such as the automotive industry less dependent on production in other regions. The EU member states’ heads of state and government want Europe to achieve a global microchip production market share of 20 per cent by 2030. According to the statement issued after the EU summit in early March, this is to back a corresponding target set by the EU Commission.

According to the Commission’s plans, public and private investments are to be stimulated in order to revive semiconductor activities in Europe. According to EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, an additional EUR 15bn are to be raised by 2030 in addition to the EUR 30bn already dedicated to investment, effectively quadrupling the production of semiconductors in the EU.

However, achieving this goal could actually take five to eight years, expects Albert Heuberger, director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits and computer chip expert. Ramping up the production capacities is a costly and lengthy process, Heuberger stressed in an interview with Reuters.

Legal note:

Prognoses are no reliable indicator for future performance.

Explanations of technical terms on investment and securities can be found in our Fund Glossary: Fund Glossary (erste-am.at)